Home » Archives for 2012

Emily D's Copyright Issues

Dear Rich: Can I quote four lines of Emily Dickinson's poetry in my novel without penalty? She lived approximately 139 years ago. We wish we could say that Emily's poetry is in the public domain but the definitive unedited versions of Dickinson's poems are said to have first been published in 1955 (even though Emily died in 1866). The 1955 edition was renewed and is under copyright until 2050 (95 years from the date of publication). (BTW, a 1998 edition -- scroll to bottom of this article -- of her poems is said to be the first version to correctly preserve Dickinson's punctuation.) Earlier edited works of Dickinson were published before 1923 and are in the public domain, so if you use these versions, you're home free. You can read more about Harvard University's claims to copyright over Dickinson's works, here. Regardless of whether the poetry is in the public domain, you have a good chance of success with a fair use argument because you are using such a short segment and for fictional purposes. You can review other fair use cases, here.

Can Husband Use Interview He Did With Time Magazine?

Dear Rich: My husband did an over-the-phone interview with Time Magazine years ago and wants to use the resulting article in a book he is writing. He didn’t sign any sort of release form for the 172-word article, which also included a photo taken by our local newspaper. Although the article is cited in MasterFILE Premier and Business Source Premier online databases as a whole article, Time claims it is part of a larger article that must be reprinted at a cost of $1,500 to $3,500 for permission. They state that “all Time Magazine articles must be reprinted in their entirety as originally appeared in the magazine along with the logo, credits and bylines.” They decline to explain this statement or to provide content until a contract is signed so it is unclear what they define as the whole article. It is also unclear to us whether they are suggesting printing an image of the article including pictures or just the text, which is what we requested. This whole interaction seems suspicious. Can my husband claim any ownership to the interview? Is it usual for a magazine to require one to reprint content one has no use for or is something strange happening here? We think your husband has a reasonable fair use argument for reproducing the Time article text in his book -- particularly if he is commenting on the article -- but we think you should first consider these issues:

Alternatively, some legal scholars argue that a better approach is that the interviewer and subject jointly create one work. Under that analysis, the interviewer and the subject are joint authors. In that case, either party can use the interview for any purpose provided that the party using the interview accounts to the other for any profits. We're not sure that applies to your situation, because it sounds as if the article goes beyond the Q-and-A format. (Anyway, you can read more on these two interview approaches at the Publaw.com site.) (Note that one court -- dealing with an interview with Ernest Hemingway -- hinted that Hemingway's failure to limit usage at the time of the interview implied unlimited use by the interviewer!)

Bottom line dept. We think this is one of those risk analysis situations. If you have a strong desire to use the article and are self-publishing to a limited audience, consider taking the risk. If you're planning on a bigger launch and a broader audience, you may want to limit reproduction to your interview responses and short snippets from the article for a stronger fair use argument. As for any photos, you would contact the local newspaper and find out whether they sold all rights in your husband's image to Time, or whether they can license the photo use to you for your book.

- Indemnity. If your husband deals with a book publisher, the publishing agreement will likely require you to pay the publisher's legal fees for any disputes caused by the book. Even if you succeed with a fair use dispute, you'll end up footing your legal bills and the publisher's, too.

- Vetting the book. Also, a publisher may require that you provide proof of permission for all non-original material. Chances are that the publisher will not want to take a chance on your fair use arguments (even if you cite the Dear Rich Staff as your source).

- Publish it yourself. If you're not dealing with a publisher, your biggest concern is whether someone from Time Magazine's licensing department will find out about your use. If so, you may likely get chased, perhaps all the way to the courthouse. If Time doesn't see it (or chooses to ignore it), you can pass Go and collect $200 (metaphorically speaking).

Alternatively, some legal scholars argue that a better approach is that the interviewer and subject jointly create one work. Under that analysis, the interviewer and the subject are joint authors. In that case, either party can use the interview for any purpose provided that the party using the interview accounts to the other for any profits. We're not sure that applies to your situation, because it sounds as if the article goes beyond the Q-and-A format. (Anyway, you can read more on these two interview approaches at the Publaw.com site.) (Note that one court -- dealing with an interview with Ernest Hemingway -- hinted that Hemingway's failure to limit usage at the time of the interview implied unlimited use by the interviewer!)

Bottom line dept. We think this is one of those risk analysis situations. If you have a strong desire to use the article and are self-publishing to a limited audience, consider taking the risk. If you're planning on a bigger launch and a broader audience, you may want to limit reproduction to your interview responses and short snippets from the article for a stronger fair use argument. As for any photos, you would contact the local newspaper and find out whether they sold all rights in your husband's image to Time, or whether they can license the photo use to you for your book.

Wants to Oppose TM Application

Dear Rich: I own a registered trademark with the USPTO. There is a new application with the USPTO which is very close to my registered trademark and can potentially cause confusion with consumers. In doing a Google search, I came across your article. I am not clear however, what form I would file with the USPTO to oppose this new application before it is too late. Can you please point me to it? You can only oppose a trademark after it has been approved for registration and has been published in the Official Gazette. It's possible -- if this is a new application as you say -- that the name has not yet been approved, or alternatively, it's possible that the application will be rejected if the examiner's research turns up your trademark and finds it confusingly similar.

Status Report. You can find the status of an application at the USPTO website. Choose "Search Trademarks" from the Trademark drop down. Choose the "Basic Word Mark Search" and enter the mark (or Serial Number if you know it). Once you get to the main page for the mark, click the "TSDR" button ("Trademark Status and Document Retrieval"). There you'll find a timeline of activity and the documents filed in the case.

The form. If the mark is approved for publication, you can file a "Notice of Opposition to Registration." Click "File a New Proceeding" on this USPTO page (see screenshot above). Choose "Notice of Opposition to Registration" from the drop down and enter the Serial Number of the trademark that you're opposing. Be aware that you're triggering an activity at the Trademark Trial and Appeals Board (TTAB). You may want to confer with an attorney before filing and get a professional opinion as to whether you have a chance at terminating the application (and also because TTAB actions are the kinds of tasks requiring an attorney's assistance).

Status Report. You can find the status of an application at the USPTO website. Choose "Search Trademarks" from the Trademark drop down. Choose the "Basic Word Mark Search" and enter the mark (or Serial Number if you know it). Once you get to the main page for the mark, click the "TSDR" button ("Trademark Status and Document Retrieval"). There you'll find a timeline of activity and the documents filed in the case.

The form. If the mark is approved for publication, you can file a "Notice of Opposition to Registration." Click "File a New Proceeding" on this USPTO page (see screenshot above). Choose "Notice of Opposition to Registration" from the drop down and enter the Serial Number of the trademark that you're opposing. Be aware that you're triggering an activity at the Trademark Trial and Appeals Board (TTAB). You may want to confer with an attorney before filing and get a professional opinion as to whether you have a chance at terminating the application (and also because TTAB actions are the kinds of tasks requiring an attorney's assistance).

Musician Claims Contract Signed Under Duress

Dear Rich: I recently resigned as a guitarist from a band I had co-founded due to harassment. Upon leaving (and under duress), I was forced to sign a 'departure contract' formed by one of the band members (no legal background). This contract had stated that I am not to be paid any money for the work I had put into the band. I was the main songwriter and producer in this project and wrote guitars, bass, drums. They gave me performance credits on the album but will not acknowledge compensation for this work. The band has been getting some strong publicity now and I would like to know what my rights are as a now departed member of the band? Should I contact a music lawyer? Should move on or wait it out? I would just like to get closure and know that the work I put in wasn't rewarded to someone else. In order to reach a state of epistemic "closure," you must "uncloud" your uncertainties (at least that's what Wikipedia says). So here goes.

Can the contract be enforced against you? A valid contract is one that a court will enforce. Some reasons your contract might not be enforceable are if (1) it violates the law or public policy, (2) there's no consideration -- you didn't receive any benefit from the arrangement, (3) the other side fraudulently induced you to sign, or (4) you were coerced (duress) into entering into the agreement. If fraud or duress are present, then you can void the contract. All parties are released from their obligations and you can pursue your claims against the band. In cases of intentional fraud—for example, if a band mate deliberately lied to induce a deal, you can elect to seek additional damages under tort law. (BTW, even if the agreement is valid, you may also have claims that the other side breached it, thereby terminating the agreement.)

What is duress? Duress occurs when a party’s consent to a contract is physically or mentally coerced. A party under duress lacks the legal free will to refuse to sign. Therefore, the agreement is not voluntary and the contract that results must be voided. Threats of physical force are rarely used as a means of inducing a contract. Instead, economic duress has emerged as a bigger issue. Economic duress (also known as “business compulsion”) occurs when, for example, a supplier of goods jacks up the price on a customer who is in desperate need of goods, or one party threatens to breach an existing contract unless the other party agrees to some further demand. But keep in mind that proving duress in a court or at an arbitration -- which is where you'll have to prove it -- requires more than threats. You'll also need to show you had no other choice but to comply, a sometimes difficult task.

Does the agreement transfer copyright? The musical compositions and the musical performances are works that are subject to copyright. In order for the band to acquire those rights, the agreement (or some other written agreement) must specifically transfer these rights. If the agreement doesn't say anything about copyright ownership, your rights in those works may be unaffected and you are probably free to register your rights in your name. Along with that, you can exploit your interest in the songs and collect royalties for their use.

Bottom Line Dept. If you want true closure, you should see a music attorney.

Can the contract be enforced against you? A valid contract is one that a court will enforce. Some reasons your contract might not be enforceable are if (1) it violates the law or public policy, (2) there's no consideration -- you didn't receive any benefit from the arrangement, (3) the other side fraudulently induced you to sign, or (4) you were coerced (duress) into entering into the agreement. If fraud or duress are present, then you can void the contract. All parties are released from their obligations and you can pursue your claims against the band. In cases of intentional fraud—for example, if a band mate deliberately lied to induce a deal, you can elect to seek additional damages under tort law. (BTW, even if the agreement is valid, you may also have claims that the other side breached it, thereby terminating the agreement.)

What is duress? Duress occurs when a party’s consent to a contract is physically or mentally coerced. A party under duress lacks the legal free will to refuse to sign. Therefore, the agreement is not voluntary and the contract that results must be voided. Threats of physical force are rarely used as a means of inducing a contract. Instead, economic duress has emerged as a bigger issue. Economic duress (also known as “business compulsion”) occurs when, for example, a supplier of goods jacks up the price on a customer who is in desperate need of goods, or one party threatens to breach an existing contract unless the other party agrees to some further demand. But keep in mind that proving duress in a court or at an arbitration -- which is where you'll have to prove it -- requires more than threats. You'll also need to show you had no other choice but to comply, a sometimes difficult task.

Does the agreement transfer copyright? The musical compositions and the musical performances are works that are subject to copyright. In order for the band to acquire those rights, the agreement (or some other written agreement) must specifically transfer these rights. If the agreement doesn't say anything about copyright ownership, your rights in those works may be unaffected and you are probably free to register your rights in your name. Along with that, you can exploit your interest in the songs and collect royalties for their use.

Bottom Line Dept. If you want true closure, you should see a music attorney.

Creating a Play About MLK and Malcolm X

Dear Rich: I am planning to present a play about Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X. Do I need permission from their estates to present a play about them? Unless you're quoting extensively from either man's copyrighted works, no, you won't need permission to create fiction based on a deceased public figure. We like this legal explanation of the rights of living and dead people used in fiction.

Art Made From Legos

Hi Rich I've read your write-up about copyright and toy photographs. What I'd like to know is what about illustrations done from toys like Lego? What if it is an illustration done for personalised canvas prints or room décor? We don't think you need to worry if you're creating LEGO artwork and reproducing it as prints.

Who gets sued? LEGO Group appears to focus its legal efforts on copycat toy manufacturers, or those who trade off its name (such as those who use LEGO in a domain name). So, we doubt LEGO Group will pursue those who create LEGO artwork unless the artist is doing something that implies that LEGO endorses or is associated with the work.

Handy disclaimer. LEGO Group provides an intellectual property statement that includes a disclaimer you can use when posting Lego material at a website -- "LEGO® is a trademark of the LEGO Group of companies which does not sponsor, authorize or endorse this site." You can probably also adopt it for many other uses. Alas, as the company points out, using this disclaimer won't shield you if you're violating the law.

PS. Based on your spelling of "personalised," we're guessing that you're writing from the UK, in which case we have to bore you with our own disclaimer -- our advice is based on U.S. law.

Who gets sued? LEGO Group appears to focus its legal efforts on copycat toy manufacturers, or those who trade off its name (such as those who use LEGO in a domain name). So, we doubt LEGO Group will pursue those who create LEGO artwork unless the artist is doing something that implies that LEGO endorses or is associated with the work.

Handy disclaimer. LEGO Group provides an intellectual property statement that includes a disclaimer you can use when posting Lego material at a website -- "LEGO® is a trademark of the LEGO Group of companies which does not sponsor, authorize or endorse this site." You can probably also adopt it for many other uses. Alas, as the company points out, using this disclaimer won't shield you if you're violating the law.

PS. Based on your spelling of "personalised," we're guessing that you're writing from the UK, in which case we have to bore you with our own disclaimer -- our advice is based on U.S. law.

Dividing BMI Songwriting Royalties

Dear Rich So we have a band and we've done most of the formalizing to make it a real company and make sure everyone is taken care of fairly. One of the things we've run into in trying to register our songs with BMI is that it wants the songwriter percentages. We are a four piece and plan to split everything equally once we are profitable (until then, the money we make from the band helps fund the band so we can keep doing band stuff) But as far as songwriters, that generally falls about 80% to one, 20% to another and all four contribute to the music composition. Lyrics are credited to the band name. Again, everyone agrees to this. But BMI wants people names and SS#'s, Tax ID #. You've said in some of your articles that the band can decide to split the royalties however they want, but how does that work from a practical standpoint if BMI wants to send checks to individual band members? Are the members supposed to sign the checks over to the band? Also, it doesn't seem to be an option to register a band as a songwriter. If BMI will only allow songwriters to be individuals, does that mean we have to have all members registered and credited 25% each so that it reflects our equal split band agreement? And then handle it internally (collecting from band members as specified in the band agreement until profitability is reached?) Performance royalties refers to the money collected by performance rights organizations like BMI and ASCAP and paid to songwriters and publishers. It's revenue derived from charging a license fee to businesses -- radio stations, stores, and taverns -- that publicly play your music. As we explain in our book -- Music Law: How to Run Your Band's Business -- even if you set up a system whereby everyone (songwriters and nonwriters) shares equally in song income, it’s still possible that a credited songwriter will receive more money from BMI. That’s because in the case of performance royalties, BMI and ASCAP split the revenue for each song and make separate payments to music publishers and songwriters. In other words, with performance royalties the songwriter’s portion is paid directly to the songwriter and does not pass through the band’s publishing company. Therefore, if a song is a big hit on the radio or in a TV show, a credited songwriter will probably receive more money than a nonsongwriter. It is possible, as you suggest, that your agreement among the band (or between the band and the publisher) could deal with this share. For example, you could create a music publisher, register that with BMI and the publisher would receive half the income. Then, the songwriters getting checks could kick those into the pot as well. Alternatively you could forget the publisher and just have the members contribute their BMI income. These alternatives require some diligence and bookkeeping which is why it's often overlooked in band situations.

-- even if you set up a system whereby everyone (songwriters and nonwriters) shares equally in song income, it’s still possible that a credited songwriter will receive more money from BMI. That’s because in the case of performance royalties, BMI and ASCAP split the revenue for each song and make separate payments to music publishers and songwriters. In other words, with performance royalties the songwriter’s portion is paid directly to the songwriter and does not pass through the band’s publishing company. Therefore, if a song is a big hit on the radio or in a TV show, a credited songwriter will probably receive more money than a nonsongwriter. It is possible, as you suggest, that your agreement among the band (or between the band and the publisher) could deal with this share. For example, you could create a music publisher, register that with BMI and the publisher would receive half the income. Then, the songwriters getting checks could kick those into the pot as well. Alternatively you could forget the publisher and just have the members contribute their BMI income. These alternatives require some diligence and bookkeeping which is why it's often overlooked in band situations.

Does Computer Calligraphy Have Copyright?

Dear Rich: I am a minister and I have copyrighted some poems. One in particular I have framed and a friend did it in calligraphy as a gift. I don't question selling this, but I do question selling my other copyrighted poems from a computer program in calligraphy. Can I sell my words in a calligraphy style from a calligraphy program? If you're asking whether there is a separate copyright in the appearance of the calligraphy -- that is, the typeface -- we're going to say, "No." Typefaces don't get copyright protection. However, there are two caveats: (1) a software program (sometimes referred to as a "font") that generates typefaces can be protected (so you want to avoid copying typeface programs or violating the terms of their license), and (2) arguably a hand drawn calligraphy that is sufficiently unique or transcends the typeface in some innovative artistic manner, may be copyrightable as a visual arts work. These exceptions don't appear to apply in your case.

Will Copyright Owner Take My Home?

Dear Rich: I'm in a band with my friend. He and I finished recording an album recently and are looking forward to releasing it as well as performing the material during live gigs. I have a serious issue with on of the tracks. It contains spoken word audio samples from a few TV programs. I took on the responsibility of research what we would need to do to get the album copyrighted and in the process found myself scared out of my wits regarding the consequences of copyright infringement. I'm having a difficult time persuading my friend that it isn't a good idea to continue using those samples. He has complied to some extent by removing most of the samples but is pushing to leave one in because it has heavy effects applied to it that he claims will obscure the original source. I also hear the argument that the program is over 20 years old and nobody will recognize it. It is changed to some extent but I'm still not convinced. It will be so easy to come after me. My name is on the recording studio receipts and we entered into a corporation together. There is all sorts of discoverable evidence against me out there. I don't want to lose my house, live with my dad, and then when he dies have what little inheritance is left taken away. The technology to automate capturing infringement issues becomes more possible by the day. What can I do? We can relate to your feelings of paranoia. We've committed infractions in our past and maybe someday they'll be discovered and we'll be off to comedy traffic school (or its moral equivalent). Sometimes we lie in bed and wonder if we did something wrong that we can't remember. That drives us really crazy, as if it will all come out in a flood of repressed liability.

Right, you had a question. Keep in mind the words of Thomas Jefferson: "How much pain have cost us the evils that have never happened." While you imagine the ultimate end-scenario -- TV-show attorneys gloat over the huge cash verdict they've inflicted on you -- the reality is far more complex. We've put together this table with our guesstimates as to the likelihood (based only on our anecdotal information and personal experiences):

Statute of Limitations. Also, the TV show can't go after for you forever. The statute of limitations for copyright infringement is three years from the date when the infringement "could have been discovered with reasonable diligence."

Bottom line dept. We agree with Joseph Heller -- “Just because you're paranoid doesn't mean they aren't after you.” But we also don't want interesting art to be unfairly sideswiped. Yes, it's always possible that something bad will happen based on your release, but we think the odds are on your side.

Right, you had a question. Keep in mind the words of Thomas Jefferson: "How much pain have cost us the evils that have never happened." While you imagine the ultimate end-scenario -- TV-show attorneys gloat over the huge cash verdict they've inflicted on you -- the reality is far more complex. We've put together this table with our guesstimates as to the likelihood (based only on our anecdotal information and personal experiences):

| Event | Odds of Happening |

| Someone associated with the 20-year old TV show will hear your track. | 1% or less. Considering the zillions of tracks out there, it’s highly unlikely anyone will hear your track unless you have a reasonable hit. |

| The person hearing the track will recognize the sample as coming from the 20-year old TV show. | 50% or less. We haven’t heard your track but you state the sample is heavily effected, making it harder to recognize. |

| The person will care enough to investigate. | 25% or less. Usually copyright owners don’t get worked up about a single quote from a show. However, there are exceptions for superstars (and of course, if you’re a superstar, you can afford to deal with all this.) |

| After investigating, the copyright owner of the 20-year old TV show determines that its worth engaging an attorney to stop your use | 50% or less. Just getting the attorney on the phone is at least $300. So there has to be a substantial concern to contact an attorney over a single quote used on a recording. |

| The attorney who is engaged writes a cease and desist letter asking you to stop and for some arbitrary payment. | 75% or less. Once engaged, it’s no big deal to write a C&D letter. But anybody can make demands. Your attorney may advise you have a good defense and suggest blowing off the demands, or alternatively reaching a peaceful settlement -- perhaps you stop distribution, destroy existing copies and pay a few thousand dollars (if any money). |

| You blow off the letter and the attorney decides to file a lawsuit. | 25% or less. It’s $5,000 to $10,000 just to file a lawsuit. Chances are the other side won’t want to risk the suit with this minor an infringement. Alternatively, they may investigate you and determine your pockets are not deep enough to pursue. |

| A lawsuit is brought and you lose. | 50%. You never know how things will go with a fair use or “de minimis” claim in court but you’ve got a decent shot with these facts. |

| After you lose, the court awards your house and inheritance to the owner of the 20-year old TV show. | 15% or less. The punishment has to fit the crime and if you didn’t make much money, a reasonable judge won’t likely hit the big buzzer for statutory damages. You keep the home and inheritance. |

Bottom line dept. We agree with Joseph Heller -- “Just because you're paranoid doesn't mean they aren't after you.” But we also don't want interesting art to be unfairly sideswiped. Yes, it's always possible that something bad will happen based on your release, but we think the odds are on your side.

Amazon Won't Link to Previous Edition

Dear Rich: Not sure if this is your department but I am an author with tax books at Amazon. Every year I publish new editions to keep the material timely. Over the years I've built up a great group of reviews and ratings from readers of the various editions. Up until this year, Amazon always linked new editions to previous editions so that the positive reviews for past editions appeared for the new one. Now, Amazon has changed its policy and no older reviews appear with the new editions. The policy punishes me and other authors who attempt to keep their books current because an outdated competing book ends up getting a higher ranking then my new edition. For example, I have one book which used to have an average 4 star rating but it has lost the stars and dropped substantially in Amazon relevance searches because older (less-positively reviewed) competing books have existing ratings. Is this okay for Amazon to do that? It seems unfair and illegal? The Dear Rich Staff definitely feels your pain. Several of our books have suffered from the same policy change and at times like this we wish we hadn't thrown away Jeff Bezos' home phone number. We also agree that this blanket policy is having a negative effect on authors who wish to present current information. That said ...

Unfair and/or illegal? Amazon's edition linking policy (stated here) may be unfair to some authors but that doesn't make it illegal. It's true that some unfair business practices violate the law because consumers are deceived. But even if some consumers are misled by Amazon's relevance searches, Amazon's overall rationale for this practice -- it wants to tie reviews of books to specific editions -- seems to have been borne from a desire to prevent consumer deception. In addition, unlike companies who engage in unfair business practices, Amazon does not directly profit from the policy. It sells the same number of books with or without the policy (just not as many of our books!)

Does the policy violate any agreements? Your publisher might be able to challenge the policy if it violates the Amazon publisher distribution agreement -- but that's doubtful because Amazon likely preserves the right to make such policy changes. The policy also doesn't appear to violate the Author Central end-user agreement.

Bottom line dept. Alas, the message from Amazon is that an author jeopardizes goodwill by updating books. There are many workarounds that Amazon could have instigated -- for example, a tag such as "This review refers to a previous edition." And some authors have reported some luck using Author Central's call-in service (while others have not). Jeff, if you're reading (and for some reason we don't think you are), keep in mind that we're also loyal Prime customers!

Unfair and/or illegal? Amazon's edition linking policy (stated here) may be unfair to some authors but that doesn't make it illegal. It's true that some unfair business practices violate the law because consumers are deceived. But even if some consumers are misled by Amazon's relevance searches, Amazon's overall rationale for this practice -- it wants to tie reviews of books to specific editions -- seems to have been borne from a desire to prevent consumer deception. In addition, unlike companies who engage in unfair business practices, Amazon does not directly profit from the policy. It sells the same number of books with or without the policy (just not as many of our books!)

Does the policy violate any agreements? Your publisher might be able to challenge the policy if it violates the Amazon publisher distribution agreement -- but that's doubtful because Amazon likely preserves the right to make such policy changes. The policy also doesn't appear to violate the Author Central end-user agreement.

Bottom line dept. Alas, the message from Amazon is that an author jeopardizes goodwill by updating books. There are many workarounds that Amazon could have instigated -- for example, a tag such as "This review refers to a previous edition." And some authors have reported some luck using Author Central's call-in service (while others have not). Jeff, if you're reading (and for some reason we don't think you are), keep in mind that we're also loyal Prime customers!

Wants to Create IPad App Based on Book

Dear Rich: I want to create an iPad App based on a book published in 1999. I contacted the Authors and they told me that the publisher owns the rights. I contacted the publisher and they said: "If you would like to make an app that uses elements of the book and is quite interactive -- those rights are controlled by the authors." Are "interactive" rights often separated from "book" rights? Yes, publishing agreements can separate interactive rights from traditional print rights. Whether an author retains interactive rights has to do with the publisher, the time when the agreement was negotiated (currently, the trend is for publishers to retain all rights), and the author's bargaining power.

Rights associated with a book are always separable. Typically, the publisher obtains worldwide English-language print rights. These are the rights to sell book versions of the work and nowadays that includes "passive" eBook versions -- for example, Kindle, ePub or Mobi book rights. These eBook formats are passive, not interactive, or as publishing attorney Lloyd Jassin states, these are "verbatim" displays of text. (Note, older "legacy" contracts were not clear about who retained these ebook rights.) Enhanced eBooks, such as are often sold in iBook or App format often include features that allow the reader to engage additional content or media or otherwise engage the user. They are considered interactive, and Jassin believes that most publishers are not in a position to exploit them. In the old days -- back in the 1990s, interactive rights might only be applicable for videogames or CD-Rom applications based on the book. But nowadays the borders are often blurred. The closer the work is to a verbatim reproduction of the text, the less likely it would be considered interactive ... Wow, have eBooks really been around for 40 years? ...

Rights associated with a book are always separable. Typically, the publisher obtains worldwide English-language print rights. These are the rights to sell book versions of the work and nowadays that includes "passive" eBook versions -- for example, Kindle, ePub or Mobi book rights. These eBook formats are passive, not interactive, or as publishing attorney Lloyd Jassin states, these are "verbatim" displays of text. (Note, older "legacy" contracts were not clear about who retained these ebook rights.) Enhanced eBooks, such as are often sold in iBook or App format often include features that allow the reader to engage additional content or media or otherwise engage the user. They are considered interactive, and Jassin believes that most publishers are not in a position to exploit them. In the old days -- back in the 1990s, interactive rights might only be applicable for videogames or CD-Rom applications based on the book. But nowadays the borders are often blurred. The closer the work is to a verbatim reproduction of the text, the less likely it would be considered interactive ... Wow, have eBooks really been around for 40 years? ...

Wants to Use Statler and Waldorf Puppets

Dear Rich: Can you tell me if I can use the original Statler & Waldorf masks on YouTube without getting into copyright problems? I want to do an item in our show (which is being planned at the moment) with us wearing the masks and do activities and visit events and comment on it! We are planning to earn money with YouTube (don't think the chance is big, but we don't want trouble if we would start earning money with it) Or is there a website where I can find out stuff about the copyright of the muppets? Statler and Waldorf -- the heckling Muppets named after New York City hotels -- are both protected under copyright law. The copyright is owned by Disney. Your use is likely to be considered infringing -- you are creating a substantially similar work that does not seem to be transformative, such that it would be permitted as a fair use. (BTW, The copyrights for Muppets that first appeared on Sesame Street are owned by the Sesame Workshop).

Bottom Line Dept. We've written several times about getting permission from Disney (put "Disney" into search box on right), but you don't need to bother reading those entries. Disney is highly unlikely to give you permission. The bigger issue is whether they'll notice your use, and if they do notice whether they'll care. As always, the more popular you become, the more likely you'll get a cease and desist letter.

Folsom Prison Diary Blues

Dear Rich: I've read your response on the publishing of Great Uncle's diaries and appreciate that. I have possession of a Folsom prisoner's diary that goes from about 1911 - 1915. It was given to me by a friend and local historian about 30 yrs ago. I've found "his last name" in the diary, but I know he was never a prisoner, so am figuring he was given it by a relative. I don't remember years ago him mentioning a familial connection, but it's logical (and not a very common name). The man who gave me the diary has been dead over 20 years now. His wife has been gone close to that long too. The diary writer is not identified. There is a short poem inside the cover though that was written by a man who's not referred to anywhere else in the book so I've wondered if he might have been its author. I haven't taken it to Folsom yet because I'm wondering if I shouldn't work too hard to know who the author really is? Am I allowed to publish a "diary by an UNKNOWN prisoner at Folsom"? Can I get a copyright to do that? The diary is either (1) in the public domain -- in which case anybody can reproduce it and nobody can claim copyright -- or (2) it is protected by copyright -- in which case ... well, read on.

Is it PD? Probably the biggest issue is whether the work is considered anonymous or not. Under copyright law (scroll down), an author's contribution to a work is “anonymous” if that author is not identified on the copies of the work. We're not sure if that's the case with the diary, but if the author is not identified, the copyright lasts for 120 years from the date of creation which is unlikely to make it public domain. If it's not anonymous and you can identify the author by perusing the diary and the author died before 1942, you can claim public domain status and freely reproduce the diary. Sound confusing ... but wait there's more. You may want to take a look at a rarely used section of copyright law, 17 U.S.C. § 302(e), which states:

(e) Presumption as to Author’s Death.— After a period of 95 years from the year of first publication of a work, or a period of 120 years from the year of its creation, whichever expires first, any person who obtains from the Copyright Office a certified report that the records provided by subsection (d) disclose nothing to indicate that the author of the work is living, or died less than 70 years before, is entitled to the benefits of a presumption that the author has been dead for at least 70 years. Reliance in good faith upon this presumption shall be a complete defense to any action for infringement under this title.Bottom Line Dept. The lineage for this publication seems so distant (and tangled) that you may decide to proceed with publication regardless of copyright law. After all, the only way someone can stop you is to demonstrate that they are the copyright owner which -- based on your info -- seems like a difficult task. If the chances of being hassled are slim, you may wish to risk it for the sake of popularizing this historic document.

Wants to Start a Magazine

Dear Rich: I want to publish a magazine. Do I need to get a copyright? I haven’t written one article, yet. How much does it cost? Where do I start? Your magazine will be protected by copyright law automatically but you can acquire additional rights by registering issues of the magazine with the Copyright Office. This circular explains the basics for magazines (serialized publications). Copyright fees change and depend on whether you are registering electronically or with paper. Nolo used to publish a good book on starting and running a magazine and you can still get copies of the last edition (2006) at Amazon. You may also want to consider trademark issues when naming your magazine. Generally you want to avoid similar magazine titles (although Nolo, our employer need not be concerned with this zine). We talked about magazine trademarks in a previous entry.

Getting Rights to Parent's Biography

Dear Rich: A family friend wrote an unpublished biography about my deceased parent some time ago and doesn’t intend to pursue publication himself. He has not registered the copyright. I would like to acquire the rights to the biography and edit it as needed, then publish some copies for the rest of my family (perhaps through Amazon). I’m planning to do an “all rights” purchase, but have a question about the copyright registration. After we sign an all rights transfer agreement, should I register the copyright under the friend’s name and then file a notice that it was transferred (I’ve seen this called an “Instrument of Recordation”)? Or should I simply file the copyright notice in my name without the notice of transfer? Assuming by "all rights," you mean that the author will assign the copyright to you -- an "all rights" agreement typically means that all of the rights to a book or artwork or music are assigned permanently for a lump sum payment -- you can file an application to register the copyright as owner. In the application, you would list the family friend as author of the work and list yourself as owner (or "copyright claimant"). During the application process, you will see a statement " If any claimant is not an author, you must include a transfer statement ..." (a shot from the online application process is shown below), and you would choose "By written agreement" from the drop down choices.

Recording the assignment. In addition to registering the work, you can also record the assignment agreement with the Copyright Office. It's not necessary but it makes the document available for public inspection and can help establish priority of ownership rights if there is a dispute. The procedures for recording transfers are explained in this circular.

Recording the assignment. In addition to registering the work, you can also record the assignment agreement with the Copyright Office. It's not necessary but it makes the document available for public inspection and can help establish priority of ownership rights if there is a dispute. The procedures for recording transfers are explained in this circular.

DVD Orgasm Techniques

Dear Rich: I'm about to go global with a DVD program that helps women feel more pleasure and achieve orgasm more easily. I'm the creator of the program and have been teaching it to small groups for years. My marketing people are asking if any of the material that I explain on the DVD has been copyrighted by other organizations. I've definitely borrowed from a lot of sources, and created my own techniques as well. I have two questions (1) Can practices and/or their names be copyrighted? When I borrow a technique called "The Deep Draw" or "The Pelvic Tilt" that has been used by a Taoist institute for decades, am I infringing, and do I need the institute's permission? If so, what if I simply call the technique something else? If it closely resembles the original technique, couldn't I still be sued? I imagine whatever you answer you give will apply to my program's original techniques as well. (2) This same Taoist institute would like to hire me as a teacher for one of their in-person events. Their contract states that I cannot teach any of their material outside of their event without the written permission of the head of the institute. Thinking I would be breaching the contract upon signing it (since I'm already teaching some of their techniques), I contacted the head of the institute. He responded with an email saying it's OK if I want to teach the techniques, but to give his institute credit. Does this email qualify as written permission? Thanks so much for your question which allowed us to legitimately put the word "orgasm" in our header, thereby achieving all our SEO goals for December in one day.

Yoga moves can't be protected by copyright. As you're probably aware, we wrote about a similar situation last year in which the so-called "owners" of Bikram Yoga techniques sued 'Yoga To The People.' We're not aware of a resolution of that dispute but shortly after posting our response, the Copyright Office weighed in with a letter stating that yoga moves, and the ordering and selection of public domain yoga exercises, are not copyrightable. This letter does not have the effect of law but the opinion conforms with most copyright experts -- physical practice techniques are not subject to copyright. Therefore, we don't believe the orgasm techniques you borrowed or invented will acquire copyright protection (though of course original illustrations or text about those techniques can be protected). As for trademarks, it's possible that, like the Bikram folks, someone can own trademark rights to the name under which a physical technique program operates -- for example "Bikram Yoga" or "Bikram's Yoga College of India." But it would be difficult, if not impossible to acquire trademark rights to the name of a specific exercise. Nevertheless, if you're paranoid, change the wording of exercises you borrow, to avoid any confusion. (BTW, patent protection for novel, nonobvious techniques is always possible ... although we have to wonder, are any sexual techniques nonobvious?)

Contracts and permission. Yes, the email should suffice as permission with a couple of caveats. (1) Even if a technique cannot be copyrighted, a person can contractually agree not to copy it. (2) Some contracts prohibit modifications unless there is a writing signed by both parties. We doubt whether this will be an issue for you and we understand the need for informality so you're fine as is. Nevertheless, if you are concerned about formalities, you may want to amend your contract to provide for the permission.

Yoga moves can't be protected by copyright. As you're probably aware, we wrote about a similar situation last year in which the so-called "owners" of Bikram Yoga techniques sued 'Yoga To The People.' We're not aware of a resolution of that dispute but shortly after posting our response, the Copyright Office weighed in with a letter stating that yoga moves, and the ordering and selection of public domain yoga exercises, are not copyrightable. This letter does not have the effect of law but the opinion conforms with most copyright experts -- physical practice techniques are not subject to copyright. Therefore, we don't believe the orgasm techniques you borrowed or invented will acquire copyright protection (though of course original illustrations or text about those techniques can be protected). As for trademarks, it's possible that, like the Bikram folks, someone can own trademark rights to the name under which a physical technique program operates -- for example "Bikram Yoga" or "Bikram's Yoga College of India." But it would be difficult, if not impossible to acquire trademark rights to the name of a specific exercise. Nevertheless, if you're paranoid, change the wording of exercises you borrow, to avoid any confusion. (BTW, patent protection for novel, nonobvious techniques is always possible ... although we have to wonder, are any sexual techniques nonobvious?)

Contracts and permission. Yes, the email should suffice as permission with a couple of caveats. (1) Even if a technique cannot be copyrighted, a person can contractually agree not to copy it. (2) Some contracts prohibit modifications unless there is a writing signed by both parties. We doubt whether this will be an issue for you and we understand the need for informality so you're fine as is. Nevertheless, if you are concerned about formalities, you may want to amend your contract to provide for the permission.

Wants to Reproduce 1890s Diary

Dear Rich: I have an unpublished diary from the late 1890s that is chock full of material of real interest to historians. It contains not a whiff of scandal or impropriety, but the owners of the copyright for this work (the diary writer's children) have no interest in publishing it themselves and will not grant permission for anyone else to publish it. If, for educational purposes, it were to be transformed into a free searchable online blog, with added photos and links to explanatory information, do you think that would pass the fair use test? We just started keeping a eDiary and we can't wait to write in today's entry that today we answered a question about somebody else's diary. Actually, we never realized how much work it is to document daily life. And we have to say it's a little disappointing sometimes to re-read it and realize that our life is basically a series of meals interrupted by commentary. (Good meals, BTW).

Right, you had a question. If the author of the diary died before 1942, then nobody owns copyright. The work is in the public domain. If the author died after 1941, the diary would still be under copyright and republication as you describe would most likely be an infringement, and not a fair use.

Right, you had a question. If the author of the diary died before 1942, then nobody owns copyright. The work is in the public domain. If the author died after 1941, the diary would still be under copyright and republication as you describe would most likely be an infringement, and not a fair use.

Can I Make a Dave Matthews Band Quiz?

Dear Rich: I am in the process of creating a Dave Matthews band quiz. It has questions from all aspects of the bands background, songs, and albums…etc. Would there be any copyright issues by creating these questions? Also, if down the line we were to charge a fee to download ‘more questions’ on this app, would that get into a sticky copyright area? Wow, the Dear Rich Staff feels old! We remember a time when you could listen to pop music without getting tested. Personally, we like the idea and we're in favor of anything that will put off dealing with life's big issues!

Right, you had a question. You can probably get away with your trivia app assuming you can make it past the app store gatekeepers (at the Apple Store and Google) and nobody from the DMB, the band's management, the band's publishing company, or the band's record label sees your app and cares enough to challenge. If the app is challenged, most likely you'll have a problem. First, the app store where it is located can terminate availability based upon its own analysis or a DMCA complaint (we've got a legal guide for app makers that explains this route), and second, the copyright owner (the band, label, publisher, etc.) could sue for copyright infringement or possibly trademark infringement. We base this conclusion on three previous cases involving trivia books (we wrote about them in this entry). We're not saying you might not eventually prevail but we would think twice before investing considerable time in commercializing this venture.

Right, you had a question. You can probably get away with your trivia app assuming you can make it past the app store gatekeepers (at the Apple Store and Google) and nobody from the DMB, the band's management, the band's publishing company, or the band's record label sees your app and cares enough to challenge. If the app is challenged, most likely you'll have a problem. First, the app store where it is located can terminate availability based upon its own analysis or a DMCA complaint (we've got a legal guide for app makers that explains this route), and second, the copyright owner (the band, label, publisher, etc.) could sue for copyright infringement or possibly trademark infringement. We base this conclusion on three previous cases involving trivia books (we wrote about them in this entry). We're not saying you might not eventually prevail but we would think twice before investing considerable time in commercializing this venture.

Which State for Governing Law or Venue?

Dear Rich: I am working on a contract where one party (the one providing the services and technology) is based in Texas and the client is based in California. Both parties want the governing law and venue to be in their respective states. Any advice? You're dealing with two concepts: (1) A “choice of law” or “governing law” provision in which the parties agree that a particular state’s laws will be used to interpret the agreement, and (2) we think when you refer to "venue," you're talking about a "jurisdiction" provision—sometimes called forum-selection clauses— require the parties consent in advance to the jurisdiction of a specific court and give up the right to complain about jurisdiction in other locations.

What really matters? Both provisions are important but of the two, we think the venue/jurisdiction provision is more important. That's because state laws may differ on some issues -- for example, Delaware favors corporations, etc.-- but for the most part choice of law doesn't make much difference. But jurisdiction provisions can create more expense and inconvenience because they determine where you must travel to in the event of a dispute. For example, a resident of California may not want to spend several weeks conducting business from a Texas hotel room, and vice versa. Despite the fact that the chances of triggering the provision are statistically very low -- so few contracts devolve into lawsuits -- lawyers like to puff up their chests and "stand their ground" on this issue with the "bigger" party usually getting its way.

Compromise? There are a couple of workarounds. You can leave out jurisdiction entirely and then either party may file where they live (assuming they can get personal jurisdiction over the other party). Or you can set up an either/or provision such that the party filing the lawsuit can choose the state law and jurisdiction. So the Texans can file in Texas, and if the Californians are suing, they can file in Cali. If you can't reach a compromise, you may have to bite the bullet and hope that you're never dragged into a lawsuit.

FYI, DR readers, two states, Idaho and Montana, refuse to honor forum selection provisions. In some other states, courts enforce these provisions only if the parties have some contact with the state beyond the contract provision—for example, they must do business with the state’s citizens even if they live (or the agreement is signed) in a different state.

What really matters? Both provisions are important but of the two, we think the venue/jurisdiction provision is more important. That's because state laws may differ on some issues -- for example, Delaware favors corporations, etc.-- but for the most part choice of law doesn't make much difference. But jurisdiction provisions can create more expense and inconvenience because they determine where you must travel to in the event of a dispute. For example, a resident of California may not want to spend several weeks conducting business from a Texas hotel room, and vice versa. Despite the fact that the chances of triggering the provision are statistically very low -- so few contracts devolve into lawsuits -- lawyers like to puff up their chests and "stand their ground" on this issue with the "bigger" party usually getting its way.

Compromise? There are a couple of workarounds. You can leave out jurisdiction entirely and then either party may file where they live (assuming they can get personal jurisdiction over the other party). Or you can set up an either/or provision such that the party filing the lawsuit can choose the state law and jurisdiction. So the Texans can file in Texas, and if the Californians are suing, they can file in Cali. If you can't reach a compromise, you may have to bite the bullet and hope that you're never dragged into a lawsuit.

FYI, DR readers, two states, Idaho and Montana, refuse to honor forum selection provisions. In some other states, courts enforce these provisions only if the parties have some contact with the state beyond the contract provision—for example, they must do business with the state’s citizens even if they live (or the agreement is signed) in a different state.

Why is Faulkner Suing Woody Allen?

Dear Rich: You have been advising people that it's okay to use quotations without infringing ... but the Faulkner estate recently sued several companies for using a Faulkner quote. Is it okay or isn't it? Speaking of Faulkner, we recently read The Sound and the Fury for the first time and we have to say that was one heck of a confusing book. We kind of liked it but if it weren't for the Cliffs Notes-style explanation in Wikipedia, we're not sure we could positively distinguish Quentin and Ms. Quentin. We tried the movie version for clarity and that was a big mistake (although that's a pretty unique cast!) Right, you had a question. Yes, the Faulkner estate recently sued over the use of two Faulkner quotes. The first lawsuit is over the quote “The past is not dead! Actually, it's not even past." The estate sued Sony Pictures over the use of that quote in Woody Allen's "Midnight in Paris," (more details here), and they also sued Northrop Grumman and the Washington Post over an ad that used a second Faulkner quote, "We must be free not because we claim freedom, but because we practice it," (more details here). The two complaints are similar (see the movie complaint; see the Grumman complaint). They both have three claims -- copyright infringement, Lanham Act violation, and commercial appropriation. We'd bet our mortgage that the copyright infringement claim will fail for the reasons expressed in yesterday's blog. As for the other two claims, we have a feeling that the estate is unhappy with the associations (military contractors, Woody Allen) and is trying to push the limits of "endorsement" claims, which could be troublesome considering that Mississippi has little precedent for right of publicity claims.

Dear Rich: You have been advising people that it's okay to use quotations without infringing ... but the Faulkner estate recently sued several companies for using a Faulkner quote. Is it okay or isn't it? Speaking of Faulkner, we recently read The Sound and the Fury for the first time and we have to say that was one heck of a confusing book. We kind of liked it but if it weren't for the Cliffs Notes-style explanation in Wikipedia, we're not sure we could positively distinguish Quentin and Ms. Quentin. We tried the movie version for clarity and that was a big mistake (although that's a pretty unique cast!) Right, you had a question. Yes, the Faulkner estate recently sued over the use of two Faulkner quotes. The first lawsuit is over the quote “The past is not dead! Actually, it's not even past." The estate sued Sony Pictures over the use of that quote in Woody Allen's "Midnight in Paris," (more details here), and they also sued Northrop Grumman and the Washington Post over an ad that used a second Faulkner quote, "We must be free not because we claim freedom, but because we practice it," (more details here). The two complaints are similar (see the movie complaint; see the Grumman complaint). They both have three claims -- copyright infringement, Lanham Act violation, and commercial appropriation. We'd bet our mortgage that the copyright infringement claim will fail for the reasons expressed in yesterday's blog. As for the other two claims, we have a feeling that the estate is unhappy with the associations (military contractors, Woody Allen) and is trying to push the limits of "endorsement" claims, which could be troublesome considering that Mississippi has little precedent for right of publicity claims.Takeaway Dept. We'll stand by our position on copyright and quotations but add the caveat that being "right" doesn't mean that copyright owners can't sue you. If you're planning an advertisement that uses a quote from someone who is alive or recently deceased, get it reviewed by a lawyer.

Calligrapher Sells Quotes

|

| Click here for more 17th Century German calligraphy |

FYI Dept. Although typefaces are not protected under copyright law, hand-written lettering (calligraphy) can be protected in some cases. In other words, you may be able to stop those who copy your hand written version of the quotation without your authorization.

Wants to Use DVD in Classroom

Dear Rich: I’m a school librarian. I recently ordered DVDs for a teacher for a class on Forensic Science, and the packaging comes with the warning “For non-commercial, private exhibition in homes only. Any public performance, classroom use, or other use is strictly prohibited" (emphasis added). Can they make the "classroom use" claim, or are they just trying to bully those who don’t know about the Section 110(1) face-to face teaching exemptions? I know the teacher in question wants to use the DVDs as an integral part of her curriculum. The Dear Rich Staff is a big fan of forensic science and we remember studying it as a co-major back at Indiana University. Alas, we never did put it to use, except perhaps to analyze the raccoon prints left on our dock recently.

Dear Rich: I’m a school librarian. I recently ordered DVDs for a teacher for a class on Forensic Science, and the packaging comes with the warning “For non-commercial, private exhibition in homes only. Any public performance, classroom use, or other use is strictly prohibited" (emphasis added). Can they make the "classroom use" claim, or are they just trying to bully those who don’t know about the Section 110(1) face-to face teaching exemptions? I know the teacher in question wants to use the DVDs as an integral part of her curriculum. The Dear Rich Staff is a big fan of forensic science and we remember studying it as a co-major back at Indiana University. Alas, we never did put it to use, except perhaps to analyze the raccoon prints left on our dock recently.Right, you had a question. If the teacher's use of the DVD qualifies under the face-to-face exemption of the copyright law (below), then it is not an infringement and you can disregard the "warning." (There is an exception, described below.)

17 USC 110 Notwithstanding the provisions of section 106, the following are not infringements of copyright: (1) performance or display of a work by instructors or pupils in the course of face-to-face teaching activities of a nonprofit educational institution, in a classroom or similar place devoted to instruction, unless, in the case of a motion picture or other audiovisual work, the performance, or the display of individual images, is given by means of a copy that was not lawfully made under this title, and that the person responsible for the performance knew or had reason to believe was not lawfully made;What if "no classroom use" is a condition of a license? There is an exception. Many companies have attempted to circumvent the copyright laws (some successfully) by forcing the consumer to license the work, rather than purchase it. However, in order to create a binding license -- one that permits a company to step in and stop so-called unauthorized uses -- the company needs to prove that the end user entered into an agreement. As we've mentioned before, the most effective end-user licenses (EULAs) require some type of actual agreement -- typically a click-to-accept checkbox or button. These mechanisms for "agreeing" come in many shades -- and courts have even enforced shrink wrap agreements in which tearing open the shrink wrap signifies that the end user agrees with the license. Check your method of ordering to determine if you agreed to any licenses and check the packaging for signs of a license agreement. As a general rule, the easier it is to demonstrate that the other party agreed to the terms and conditions, the easier it will be to enforce the agreement. If the license is part of the packaging, it should be prominent and obvious that breaking the seal enters the end user into a license agreement. Our gut feeling is that the "warning," by itself, probably has little legal effect.

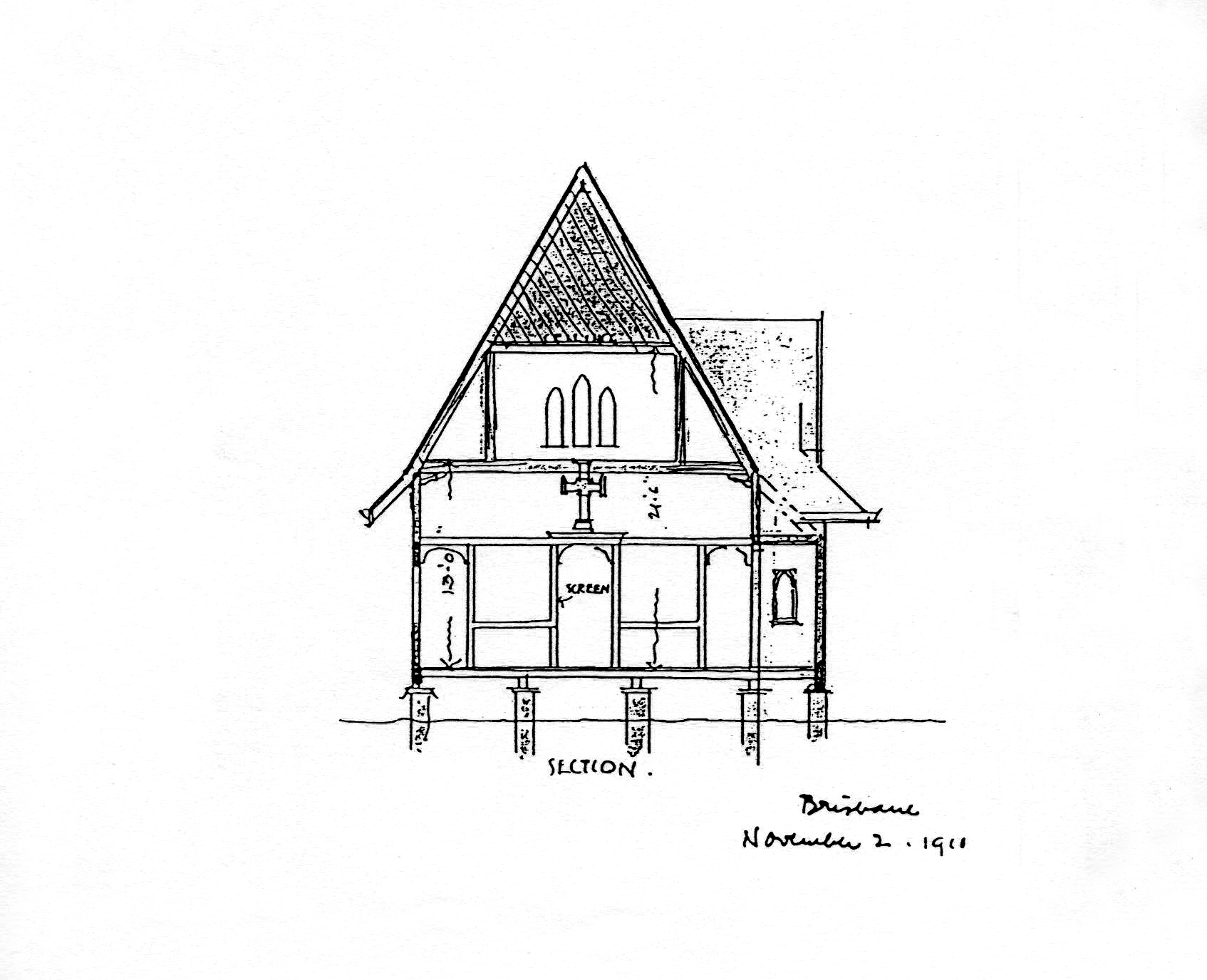

Wants to Publish 100-Year Old Floor Plans

Dear Rich: I own a large collection of early 1900's architectural drawings and photographs of residential homes. Most of these homes were built during the 1920's and some are now owned by famous celebrities. This collection of drawings and photographs was left to me by an architect relative who died more than fifty years ago. I'm working on a book of this architecture and would like to display many of the drawings and photographs of these homes in the book and on the Internet. I believe the architect, or their heir (me, in this case) owns the rights to architectural drawings and ideas but I'm not sure of the legal issues of displaying these images to the public. Could privacy be an issue here even though all the original owners of these mansions are long dead and the homes are no longer owned by that family? Do I have the right to publish room layouts, dimensions and photographs of these homes? Some of the homes have been torn-down so I assume publishing anything about those would be safe but what about those that are still standing and occupied? I'm also concerned about losing the rights to these things if I put them online. Couldn't someone else copy them and claim a copyright for either the architectural idea or the image itself? Do I even own the copyright on these drawings and photographs and architectural ideas just because I own the paper they are printed on? So many questions, so little time. Here goes: The photos and architectural drawings may be protected under copyright if the author died after 1942 and either (1) the works were never published, or (2) they were published after 1922 and properly renewed. If the works meet these criteria, and you are the heir to the copyright owner’s estate (and can prove it), you can register copyright in your name and stop others from copying the works.

Copyright for architectural works. Architectural drawings were not classified as protectable works until December, 1990. Prior to that, courts tended to protect architectural blueprints. The extent of protection may depend on how distinctive or elaborate the plans are, but it's likely the works you describe will meet the standards for protection.

Privacy. We don't believe that publication of architectural drawings would give rise to a successful invasion of privacy claim because the publication doesn’t disclose personal facts, or intrude into personal affairs. Even if we are correct, however, a wealthy homeowner could always still mount a tort claim. You may lower the chances of such a suit by not mentioning the names of the persons presently living at the home.

Copyright for architectural works. Architectural drawings were not classified as protectable works until December, 1990. Prior to that, courts tended to protect architectural blueprints. The extent of protection may depend on how distinctive or elaborate the plans are, but it's likely the works you describe will meet the standards for protection.

Privacy. We don't believe that publication of architectural drawings would give rise to a successful invasion of privacy claim because the publication doesn’t disclose personal facts, or intrude into personal affairs. Even if we are correct, however, a wealthy homeowner could always still mount a tort claim. You may lower the chances of such a suit by not mentioning the names of the persons presently living at the home.

Cosmetic Tattoo Business Snafu

|

| photos by Ohmargieg |

Right you had a question. You probably don't have any recourse against your supposed partner. You might have a better postion if (1) you made a financial investment or took some other action in reliance upon the agreement (2) you provided trade secret information about your business idea and the other party agreed to keep that information confidential, (3) you had a proprietary idea (one that could be protected under copyright, patent or trademark law) for a business and it was stolen or (4) you formally created a business entity such as an LLC or corporation which required state registration. We weren't sure what you meant by "register the business with companies house" until we Googled it and realized you were in the UK. Although we have similar legal systems, our answers are based on U.S. law.

Wants to Create Mobile Movie Trivia App

Dear Rich: We want to create a trivia game for mobile devices. The topic is movies characters. We want to show some drawings too (made by our artistic staff). Is there a copyright problem with using their names and showing drawings representing them, even if some characters are from animation, or fantasy movies? If permissions were like traffic signals, our staff would give your mobile app a yellow light. You're probably fine but proceed with caution. As we've discussed before, movie characters are often separately copyrightable from the movie(s) in which they appear. If the character is separately protectable (or if the still used from the movie is protectable), your drawings would likely be derivatives and the combined use of character name and image could be considered infringing. We say "could be" because this legal analysis is likely to be overkill. If we examine the cases in which trivia merchandise is pursued (as we did at a recent post), it's usually because it focuses on one movie, TV show, or book. That is, the owner of the movie, book, or TV show feels as if their work is being ripped off. We think you can conclude that as long as you don't focus your trivia game on one work or character, then the odds diminish as to whether anyone will be motivated to chase you down (and your chances of claiming fair use increase).

Failure to Respond to a Permission Request: What Does it Mean?

Dear Rich: In a recent post, you made the comment that it’s inefficient for large companies to deal with and track minor permissions requests. I’m curious about situations where a request is made but no response is given. While I know a lack of an answer does not equal permission, does the lack of an answer do anything to strengthen the fair use argument? In other words, would my ‘good faith effort’ in trying to seek permission weigh in my favor if I resorted to a fair use argument? A related question, regardless of how the previous question is answered, is it appropriate to associate no response with a lack of care about the particular request, thereby indicating a lower risk of being pursued? A failure to respond to a fair use request should not strengthen or weaken a fair use defense. For example, in the Pretty Woman case (in which rappers borrowed the first line of the Roy Orbison song), the music publisher had refused the permission request. Despite the refusal, the rappers went ahead with their plans, and the Supreme Court ultimately determined that it was a fair use. The reason why the copyright owner's response won't matter is that a fair use analysis happens after a court has determined that infringement has occurred. In other words, by the time a court looks at fair use, permission doesn't matter.

Why seek permission? If permission is unnecessary for a fair use defense, why ask for it? First, acquiring permission bypasses the need for a legal dispute (and the uncertainties and expenses associated with it). Second, seeking permission also demonstrates your good faith and may mitigate the damages assessed if your fair use defense fails and there is a negative decision against you.

Does a failure to respond to a permission request mean that there is a lower risk of being pursued. We doubt it. Although, as anecdotal evidence, we can offer this story: Our mom called a lawyer at a well-known movie company for permission for her nonprofit to use a licensed character in a presentation. His response, "You never made this call." In other words, having to say "no," would have obligated the attorney to follow up.

FYI Dept. -- Silence doesn't mean legal assent. We remember getting letters from lawyers that would say things like, "A failure to respond shall confirm blah, blah, blah." But 99.9% of the time that's just not the case. Inaction, or silence rarely triggers any legal conclusion (either affirmative or negative). For example, there's a famous 19th-century English contract case in which a man offered to buy a horse and stated that unless he heard otherwise from the seller, “I consider the horse mine.” The British court ruled that his assumption didn’t create a contract; the other party’s acceptance had to be clearly expressed.

Why seek permission? If permission is unnecessary for a fair use defense, why ask for it? First, acquiring permission bypasses the need for a legal dispute (and the uncertainties and expenses associated with it). Second, seeking permission also demonstrates your good faith and may mitigate the damages assessed if your fair use defense fails and there is a negative decision against you.

Does a failure to respond to a permission request mean that there is a lower risk of being pursued. We doubt it. Although, as anecdotal evidence, we can offer this story: Our mom called a lawyer at a well-known movie company for permission for her nonprofit to use a licensed character in a presentation. His response, "You never made this call." In other words, having to say "no," would have obligated the attorney to follow up.

FYI Dept. -- Silence doesn't mean legal assent. We remember getting letters from lawyers that would say things like, "A failure to respond shall confirm blah, blah, blah." But 99.9% of the time that's just not the case. Inaction, or silence rarely triggers any legal conclusion (either affirmative or negative). For example, there's a famous 19th-century English contract case in which a man offered to buy a horse and stated that unless he heard otherwise from the seller, “I consider the horse mine.” The British court ruled that his assumption didn’t create a contract; the other party’s acceptance had to be clearly expressed.

Wants to Use Lion King Screenshot

Dear Rich: I want to use a YouTube screenshot of Lion King, the scene where he talks to the ghost of his father, as an example of human trait of denying death, and clinging to dead parents. From what I've read, I think I'm clearly within "fair use," but would still like permission. When I mail my request, I do not know whether to include the screenshot, or just a description. Would just having the screenshot be considered an infringement? We wouldn't worry about possessing the screenshot or furnishing it as part of request for permission. That's fairly common when asking for permission and Disney is not going to call in the lawyers over that.

Fair use? You haven't explained in what media you intend to use the screenshot or what size. In general, your intended republication sounds like a fair use -- you're using the photo for a transformative purpose, to comment on an anthropomorphic personality trait. Of course, the less prominent your use (for example, not on the cover of a book or your use of a smaller image versus a large one), the more likely the fair use defense may work. But as we always say, you can only prove fair use in court ... which means that if Disney learns of your use (and cares) you'll have to give up on the imagery or go toe-to-toe (or is it head-to-head) with the Disney legal team.

Speaking of the Disney legal team ... We have a feeling that unless you're representing a major website, book publisher, or film production company, Disney is unlikely to respond to your permission request (or if they do, they will deny it). That's because it's generally inefficient for the company to deal with and track minor requests, and much easier to simply deny them. In that case, you'll be in the odd position of having been told by Disney that you can't use it. Because of that potential result, many people with self-published or independently distributed works bypass the permission request. These people don't expect Disney will learn of their use and (like you) they may have a decent fair use defense as backup.

Fair use? You haven't explained in what media you intend to use the screenshot or what size. In general, your intended republication sounds like a fair use -- you're using the photo for a transformative purpose, to comment on an anthropomorphic personality trait. Of course, the less prominent your use (for example, not on the cover of a book or your use of a smaller image versus a large one), the more likely the fair use defense may work. But as we always say, you can only prove fair use in court ... which means that if Disney learns of your use (and cares) you'll have to give up on the imagery or go toe-to-toe (or is it head-to-head) with the Disney legal team.

Speaking of the Disney legal team ... We have a feeling that unless you're representing a major website, book publisher, or film production company, Disney is unlikely to respond to your permission request (or if they do, they will deny it). That's because it's generally inefficient for the company to deal with and track minor requests, and much easier to simply deny them. In that case, you'll be in the odd position of having been told by Disney that you can't use it. Because of that potential result, many people with self-published or independently distributed works bypass the permission request. These people don't expect Disney will learn of their use and (like you) they may have a decent fair use defense as backup.

Wants to Write a Story About Troll Dolls

Dear Rich: My daughter is a collector of Troll dolls, and I am a published fiction-story writer. Do I need permission to write a fiction story about Troll dolls? You're free to write about the Troll dolls but there may be limits on how far you can go when exploiting your story.