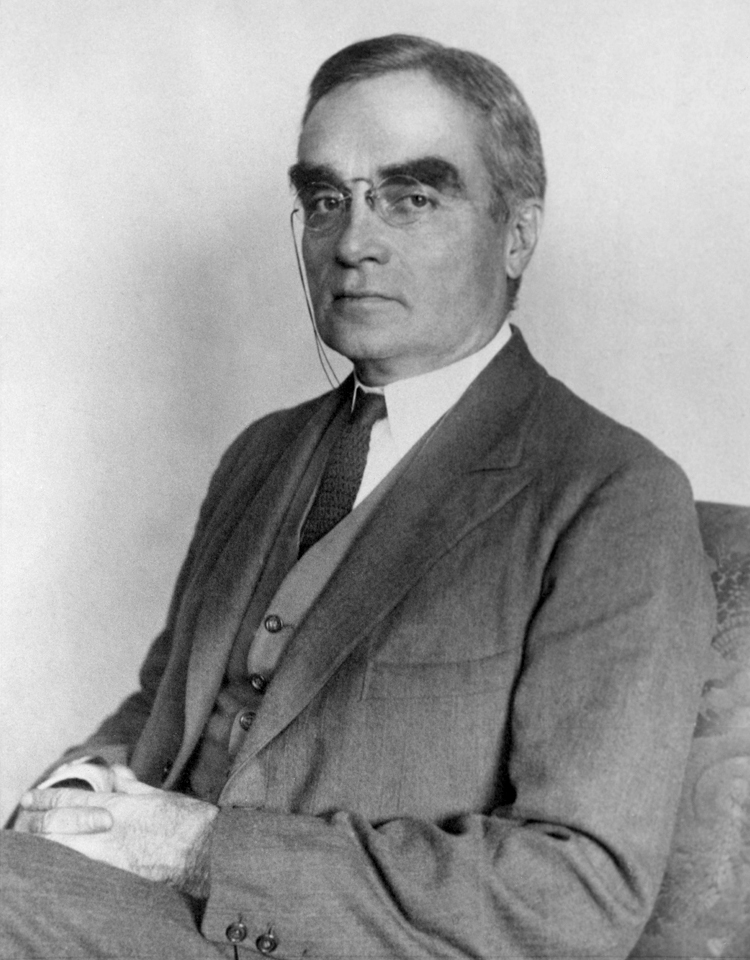

Wow are we annoyed! We missed celebrating Chester Carlson's 100th birthday last month. Oh well. Here's an article we recently wrote about one of the coolest inventors ever.Snazzy inventions aren’t just for science geeks and movies about time travel—they also changed the way that law offices did business in the twentieth century. The ballpoint pen made it easier to sign contracts, by eliminating attorney’s fountain pens and inkwells. Post-Its made it possible to flag legal errors and provide handy “sign here” notes. Liquid Paper enabled secretaries to make corrections (instead of retyping whole briefs), the Rolodex simplified keeping client information, and, of course, Scotch tape enabled lawyers to tape together legal bills after clients ripped them to shreds.

But one invention—the Xerox 914—turned out to be the most profitable device to drop into the law office. And surprise, surprise, it was invented by an attorney.

Like many people who worked with legal documents, Chester Carlson was frustrated by inefficiency. Back in the early 1930s before he became a lawyer, Carlson worked in the patent department of Bell Laboratories. He quickly tired of copying patents using carbon paper. The reproductions were time-consuming and prone to errors. (For those too young to remember, copies used to be made by jamming sheets of carbon paper between sheets of paper, stuffing them into a typewriter, and typing firmly enough so that the carbon made imprints—then swearing up a storm if there was a typo.)

At about the same time, Carlson’s hypercritical mother-in-law moved into his apartment. To avoid her unpleasant nightly tirades, Carlson enrolled in law school. While hand-copying passages from law books one night, Carlson again ran into the same frustration. Why wasn’t there a simple method of reproducing copies on paper? Carlson began to pursue an obscure idea—a process that would fuse fine black powder to paper using electrostatic charges. Carlson originally called his process “electron photography,” and then nicknamed it xerography (from the Greek words xeros (dry) and graphein (writing).

In 1937, by which time he was a patent attorney, Carlson perfected his theory and used his legal drafting skills to patent his revolutionary process. But he still had no actual proof that it worked. He offered his patent to IBM for a $10,000 advance and 5% royalty—in hindsight, one of the best offers of the twentieth century—but IBM passed. (Twenty years later, IBM still failed to see the potential when it reviewed the first Xerox copier and concluded that the device “has no future in the office copying market.” Ouch!)

It wasn’t until 1945 that Carlson partnered up with a nonprofit R&D firm in Ohio, which improved on the invention and licensed manufacturing rights to the Haloid Company, a tiny photographic paper manufacturer in Rochester, New York. Things dragged on until the mid-1950s when—just as Carlson’s initial patents were expiring—the Haloid Company (now renamed Xerox) perfected

Carlson’s process and tested it in nearby offices. Xerox knew it had a hit when the testing companies asked to keep their demo machines.

The debut of the Xerox 914 was one of those rare moments in inventing history when a device transforms the environment in which it is placed. Xerox believed that businesses would use the 914 primarily to make duplicates of outgoing correspondence. They never imagined that employees—no longer encumbered by messy and time-consuming copies—would use it for internal document reproduction, such as memos, reports, newsletters, and even personal documents or their faces and other body parts. The result was an explosion of office and personal copying. Within seven years of its introduction, Xerox was the 15th largest publicly owned company in the United States.

It’s said that the business of law is really about selling paper to clients; and the Xerox machine put that principle into overdrive. The law firms devised a clever system of markups. Initially, they leased copiers and paid per copy, allowing them to mark up and pass along those charges to clients. But even after law firms began to own their photocopiers, they retained the per-copy charges for clients. A few cents per copy may not seem like much at first, but hey, what if everyone is suddenly buried in paper?

And buried they are. Consider, for example, when one business sues another. As a normal part of the pretrial discovery process, in which each side asks to see evidence held by the other, attorneys review the other side’s relevant memos, phone records, financial records, and other documents. With piles more photocopied documents at each business, however, it creates an exponential increase in the size of discovery requests—literally boxes, and sometimes trucks of documents being sent back and forth. To deal with this paper explosion, law firms added more staff, thereby increasing the billing. In short, Xerox had created a cash machine for law firms.

The copier also triggered illegal activity (always a boon for lawyers). For example, there was office espionage, loss of trade secrets, and even fraud (for those who understood how to create fake photocopied documentation). The Xerox machine launched many copyright lawsuits: for example, a series of cases where authors and publishers protested the fact that people—students and teachers, in particular— were no longer buying their books and scholarly journals, but simply slapping a borrowed original onto a copy machine. Legislators took the device into consideration when creating the 1976 Copyright Act, by including provisions on academic photocopying. Although we now take the photocopier for granted, it was essentially the original VCR or Napster—a device that, for the first time, put infringement into the hands of ordinary Americans.

Carlson earned millions from Xerox, but never measured success by money. He had spent his childhood in poverty—during his last year in high school he lived in a converted chicken coop—and had a goal to rid himself of his wealth before he died. He spent his final years getting rid of his royalties via charitable contributions and pursuing spiritual goals. His process—which remains virtually unmodified from his 1937 patent—continues to supply copies to his legal brethren via photocopiers, laser printers, and fax machines.