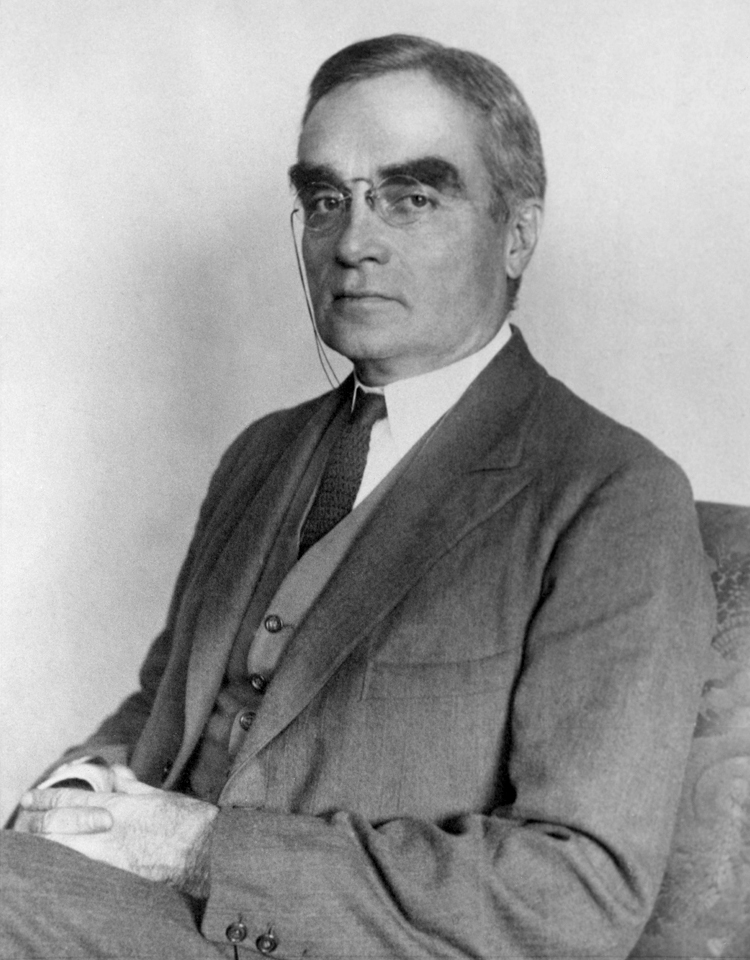

Reiss v. National Quotation Bureau, Inc. Learned Hand decided Reiss in 1921, a remarkable year for the arts -- Picasso's Three Musicians debuted as did Mondrian's Red, Yellow, and Blue, and Eubie Blake was having a hit with his ragtime jazz piano roll for I'm Just Wild about Harry. Within a year of the Reiss decision, James Joyce would publish Ulysses.

In Reiss, a man had published a book of 6,325 “coined” or nonsense words that could be used as a secret code by telegraph operators (who would assign private meanings to the meaningless words). A publisher copied the code words and when sued, defended himself by arguing that copyright could not protect the book because the code words had no "meaning." Judge Hand established a principle that we now take for granted: copyright law does not impose a standard of comprehension on works of authorship. Like Picasso, Mondrian, Blake and Joyce, Hand understood that the narrative sensibility (whether in stories, imagery or music) was no longer essential, if it ever was.

"I see no reason why words should [not be protected] because they communicate nothing. They may have their uses for all that aesthetic or practical and they may be the productions of high ingenuity or even genius."The code words, said Hand, were like "an empty pitcher" in that they had a prospective meaning, but as yet had not received it.

"Not all words communicate ideas; some are mere spontaneous ejaculations, some are used for their sound alone, like nursery jingles, or the 'rhymes of children in their play. Might not some one, with a gift for catching syllables, devise others? There has of late been prose written, avowedly senseless, but designed by its sound alone to produce an emotion. Conceivably there may arise a poet who strings together words without rational sequence - perhaps even coined syllables - through whose beauty, cadence, meter, and rhyme he may seek to make poetry."Fifty-seven years after Reiss was published, it became a cornerstone for protecting computer code; it was used by the CONTU Commission to validate protection of computer code, and served as precedent for the seminal case protecting operating systems and object code. Thanks Judge.

0 comments:

Post a Comment