Dear Rich: I was told that a single book title cannot be registered as a trademark, only a series? How many books make a series? How much new material has to be added to subsequent books in the series? You are correct that a single book title cannot be registered as a trademark with the USPTO. That rule is typically applied by USPTO examiners not just for books, but also for any "single creative work," including sound recordings, downloadable songs, downloadable ring tones, videocassettes, DVDs, audio CDs, and films. (BTW, the USPTO does not consider computer software, computer games, coloring books, puzzle books, and activity books as "single creative works" so you can register the title of these if there is only one.)

How many is a series? Apparently, two separate creative works is enough to establish a series according to the Manual of Examining Procedure. However, you will want to make sure that the submissions are significantly different in content -- for example, it's not simply the same book, but slightly revised. Also, the title (or portion of the title) used as a trademark must create a separate commercial impression (TMEP 1202.08(d)(i)) -- meaning that the size, font, and color used for the mark being registered for the series should be separable or different from the remainder of the title.

Home » Archives for August 2012

Can I Use Watercolor Versions of Photos?

Dear Rich: I am doing a documentary on a school board desegregation lawsuit that began in 1962 and ended in 2010. Three of the attorneys are still practicing and one is a state appellate court judge. I downloaded their pictures with their bio. I then sent the pictures to a watercolor artist who made a portrait of them in an impressionistic style so there are similarities such as direction of the subject's head and direction of eyes and other features and other general similarities such that you could presume that the watercolor portrait came from the downloaded pictures. The websites where I got the pictures (the law firms and courts) are openly available on the Internet and I am going to release my documentary on the Internet completely free of charge. I was planning on having these watercolor portraits in a dedicated frame as I do a voice over about the role each one played in the case. Is this fair use? If the similarities are like those between our watercolor (left) and the unadorned version (right), then it's probably not fair use. Of course we can't say for sure because that may depend on various factors such as: how long the watercolor appears in the film (the less time, the better your outcome), the size within the frame, (smaller is better for fair use purposes) and whether the artist's modifications result in a change in perspective -- that is, a person viewing the watercolor gets a different impression of the subject than they might from seeing the original photograph. There are various cases in which artwork is modified (and a derivative is created) and the results are not considered fair use. (You can read about similar cases here).

What really matters ... It doesn't matter that the photographs are widely available on the Internet or that you are offering your documentary for free. The copyright owner (either the photographer, or the party who commissioned the picture) can still pursue you for infringement. We're not so sure that will happen as the owner may never see your work (and may not care, either). But defending fair use is not something you'll want to do. If you don't want to ask for permission, you should limit the use of the imagery to the shortest screen time possible and (if possible) limit the size so that the image fills only a portion of the screen. That may strengthen your position ... should you need to defend it.

What really matters ... It doesn't matter that the photographs are widely available on the Internet or that you are offering your documentary for free. The copyright owner (either the photographer, or the party who commissioned the picture) can still pursue you for infringement. We're not so sure that will happen as the owner may never see your work (and may not care, either). But defending fair use is not something you'll want to do. If you don't want to ask for permission, you should limit the use of the imagery to the shortest screen time possible and (if possible) limit the size so that the image fills only a portion of the screen. That may strengthen your position ... should you need to defend it.

Wants to Make Movies of Customized Puppets

Dear Rich: I have a question about puppets! My friend and I are planning to start a YouTube channel where we upload puppet show videos we shot. Some of the puppets are completely original, hand-made. But some puppets are bought - from Silly Puppets, Sunny Puppets and some Muppet Whatnots that we customize. Of the bought puppets, some are heavily modified, some lightly modified, some just in costume changes. So my questions are somewhat progressive: (1) Do we have the right to put up videos online that use these commercial puppets? We don't want to get a large body of work done only to be later told we can't use any of it. (2) Should we list the manufacturer of the puppets in the credits? (3) If we start to get revenue sharing from YouTube from advertising (for many hits), do we have the right to that money or would the puppet manufacturers have some right to it? (4) If it someday came to the point where we were making direct money from our show idea (DVD sales, TV series, whatever), would their be legal issues and questions about claims to the profits? The short answer is that we don't know what will happen. There are too many variables to give you the thumbs up. We do know that the less success you have, the less hassles you'll endure. So, if things start taking off, you should switch to all-original and heavily modified puppets. Let's break out the factors.

- The puppet maker has an enforceable copyright. Assuming there is sufficient originality in the design, (sock puppets might not count), the manufacturer owns copyright in the puppet's appearance. As our readers know, purchasing a copyrighted work doesn't automatically convey the right to publicly display or publicly perform the work. So, assuming the puppet is protected by copyright, the manufacturer controls rights and can stop unauthorized uses. Okay, but ...

- The puppet maker may be reluctant to enforce rights. It would put a damper on puppet sales if a manufacturer were to clamp down on every customer who made a YouTube puppet video. So, as a general proposition, if you don't attract too much attention, and you don't upset anyone, your videos will stay posted and undisturbed. It's even possible that some manufacturers may never care. (We wouldn't go so far as to urge the use of copyright-protected puppets for their SEO value.)

- Customized puppets make it more confusing. Obviously original puppets are no problem, as are puppets that are so customized you can't recognize the orignal. (We also don't think that creating a Muppet Whatnot amounts to original authorship). But, in general, creating a derivative puppet won't shield you from infringement claims.

- Puppet makers may take action ... A puppet maker is more likely to take action if (1) you used the puppet in a scandalous or offensive manner (which is why attribution may not be a good idea); (2) you capitalized on one or two puppet characters -- for example created a popular series with two Silly Puppets -- thereby affecting the ability of the manufacturer to license or otherwise exploit the puppet, or (3) you used the manufacturer's trademarks in the titles of your works. Note, though owners of puppet characters have exerted rights on YouTube, we believe the current tendency is to tolerate many types of infringements. In other words, you may not have a chance to earn YouTube ad revenue because the owner of the puppet copyright would already have a hand in the till.

Wants Trademark Rights to Sports Star Nickname

Dear Rich: I read your entry about sports stars and nicknames where you say that the sports star or team has the rights to the nickname. Here are my questions:

(1) What if the nickname has already been bought and sold nationally and the artwork associated with the nickname is copy-written as well as having the nickname trademarked? (Common Law TM'd/© for some time before it caught on - Registered TM in process)

(2) I realize that the player most likely owns their likeness, but wouldn't the person who created a potential $-maker of a nickname for them and got the ball rolling on that side of things, be entitled to something? Thanks for checking out our previous entry, which was unusually popular. For that reason, we're happy to run through your questions in the hopes that it will churn up our metrics. (BTW, there's a difference between a copyrighter and a copy-writer. Check with Don Draper for more details. Also, there are some among us who do not believe trademark (or copyright) should be used as a verb.)

Question 1: Sorry, but we don't know what you mean by "bought and sold nationally." If the artwork is protected by copyright , then the owner of copyright can stop others from using it. But that doesn't mean the owner can use the artwork as a trademark. Imagine that you created artwork for the new Starbucks logo. You owned the copyright and wanted to use that on a line of coffee mugs. Starbucks would have little trouble stopping you. As for common-law copyright, that's not relevant to your discussion for reasons we don't have time to explain. "Common-law trademarks" (that is, unregistered trademarks) are subject to most of the same rules as registered marks and a sports star or team could most likely stop competing uses.

Question 2: There's no question that fans of sports stars love those nicknames, but ultimately anyone who commercially promotes a sports star's nickname is trading off the sports star's success. The nickname-exploiters didn't "get the ball rolling," they hopped on the ball for a ride. (Would the nickname have any value if the star hadn't become famous?) Trademarks reward commerce, not creativity and on that basis, the sports star (or the team or league, as the case may be) will most likely prevail in disputes.

(1) What if the nickname has already been bought and sold nationally and the artwork associated with the nickname is copy-written as well as having the nickname trademarked? (Common Law TM'd/© for some time before it caught on - Registered TM in process)

(2) I realize that the player most likely owns their likeness, but wouldn't the person who created a potential $-maker of a nickname for them and got the ball rolling on that side of things, be entitled to something? Thanks for checking out our previous entry, which was unusually popular. For that reason, we're happy to run through your questions in the hopes that it will churn up our metrics. (BTW, there's a difference between a copyrighter and a copy-writer. Check with Don Draper for more details. Also, there are some among us who do not believe trademark (or copyright) should be used as a verb.)

Question 1: Sorry, but we don't know what you mean by "bought and sold nationally." If the artwork is protected by copyright , then the owner of copyright can stop others from using it. But that doesn't mean the owner can use the artwork as a trademark. Imagine that you created artwork for the new Starbucks logo. You owned the copyright and wanted to use that on a line of coffee mugs. Starbucks would have little trouble stopping you. As for common-law copyright, that's not relevant to your discussion for reasons we don't have time to explain. "Common-law trademarks" (that is, unregistered trademarks) are subject to most of the same rules as registered marks and a sports star or team could most likely stop competing uses.

Question 2: There's no question that fans of sports stars love those nicknames, but ultimately anyone who commercially promotes a sports star's nickname is trading off the sports star's success. The nickname-exploiters didn't "get the ball rolling," they hopped on the ball for a ride. (Would the nickname have any value if the star hadn't become famous?) Trademarks reward commerce, not creativity and on that basis, the sports star (or the team or league, as the case may be) will most likely prevail in disputes.

Wants to Use Homer Simpson's Medical Records

Dear Rich: I'm currently writing a book on computer databases and I need a list of fictional names to simulate a medical records database for one of the chapters. I thought it would be amusing to use a list of characters from the Simpsons, with fictitious data about health conditions for use in the exercises for that chapter. If I cite the names as copyrighted by Fox, am I allowed to do that? Considering the zillions of Simpsons infringements, it's possible, though statistically unlikely, that the Simpsons' lawyers will choose to hassle you over your proposed use (BTW, attribution usually doesn't make much difference.) If by some bizarre chance you were hassled, and you could afford to take on the case, you have a reasonable claim for fair use (especially if you're only using the names, not the imagery). What would increase your chances of getting hassled would be if you used the Simpsons in connection with your promotion or advertising of the book, or if you used the characters as the centerpiece of a book -- for example, Simpsons Health Tips or Homer Simpson Diet Tips. Otherwise, your proposed use should fly safely below the Fox lawyers radar. We posted more on the Simpsons in a previous entry.

Can I Use Photo of '54 Buick?

Dear Rich: I recently went to a public event that included an antique car show. There were no restrictions about photography. I shot many images of many cars. I handed out my card to the car owners when I could find them and told them they could see some of the photos on my web site and purchase them too. Many of my photos are just detail shots, using the shapes, forms and color to make an interesting composition. A week after the show, I get an email from the owner of a 54 Buick asking me to please remove the photograph of his car from my web site. He said I did not tell him I was a company selling photographs. I must not have told him they could be purchased. It was only then that I learned of the “property release” issue. I was dumbfounded and naïve to this but it just didn’t seem right. The photo in question is not even the whole car, it could be any 54 Buick. But even if it’s the whole car, what’s my risk? We can only think of a few situations where you might be at risk: (1) if the cars contained artsy creative custom detail work that amounted to separate artistic expression (in which case there may be a copyright claim); or (2) if the organization that presented the custom car show placed restrictions on photography (in which case you would have breached the contract and the organization -- not the car owner -- would have a claim); or (3) the focus of your work was car logos and you sold these images on merchandise -- for example, selling t-shirts with the Chevrolet logo (in which case, the car company -- not the car owner -- might bring a trademark claim). Otherwise, we don't see a problem.

What about the property release? A property release is typically used to allow someone permission to enter property (typically, a house or building) and use the location in a photo or film. A property release wouldn't be required at an auto show show (unless the venue had photo restrictions).

What about the property release? A property release is typically used to allow someone permission to enter property (typically, a house or building) and use the location in a photo or film. A property release wouldn't be required at an auto show show (unless the venue had photo restrictions).

Wants to Use Quotes About God

|

| "God the Father" by Pompeo Girolamo Batoni |

Google's Prior Art Button

Google announced a new feature for their patent search tools. It's a button that appears on the pages of certain patents. Clicking the button triggers a search based on key terms from the patent. What's nice about the search is that it only retrieves documents from before the date that the patent was filed. This may prove helpful for inventors seeking out prior art. Check it out.

She Wants to Publish Great Uncle's Diaries

Dear Rich: My grandmother who has since passed away gave me a series of illustrated diaries created by my Great Uncle who was a talented artist, movie producer (1920s +). He has been gone since the 70s and had no living spouse or children. His works are so beautifully done and have great detail that would certainly be enjoyed by many plus the historical information they contain. I would love to have them published however, I am obviously not the creator. How does the copyright process work when something is passed down by family (not mentioned in any will) and the author/artist/creator is deceased? Your great-uncle's diaries deserve to be published so let's figure out a way to do that.

Try to determine ownership. It's not clear whether your great-uncle had a will (and the copyright wasn't mentioned in it) or whether he didn't have a will. If he had a will, and the copyright wasn't mentioned, it would likely go to whoever received the residuary estate. If he didn’t have a will, you would need to map out the family tree and determine what blood relatives were alive at the time your uncle died. For example, if your uncle had no will and your grandmother was his closest living blood relative at the time he died she probably became copyright owner under the rules of intestate succession (you can see how it works if he died in California). So, initially the copyright went to whoever received the residuary estate or by intestate succession. If it went to your grandmother, then, upon her death, the copyright would have passed according to her will, or if she didn't have a will, intestate succession would kick in again.

The diaries and the copyright. Your grandmother may have given you the diaries as a gift but giving you the physical possession of the diaries is different than giving you the copyright. It's the difference between giving someone a painting, and giving someone the right to reproduce the painting. That's why copyright transfers must be proven by a written document. By the way, the unpublished diaries are protected under copyright for seventy years from your uncle's death.

If this seems too confusing ... If this seems overwhelming, keep in mind that what you’re really trying to determine is whether there is a relative who will object to your claim of ownership or seek a share of any revenue from the publication. So, if you don’t expect the publication to be a major source of revenue, it’s likely you can proceed without bothering with most of these ownership rules because battles usually only arise when a big bankroll is at stake. If the diaries generate revenue and you're still unsure about ownership, put the money in an account for a period of several years in case someone appears out of the woodwork to challenge your claim. That good faith effort will likely go a long way towards resolving the matter.

Copyright applications. By the way, if you should file a copyright application, you would list your uncle as author and yourself as copyright claimant and under “transfer statement,” you would choose "By Inheritance" (as shown above). Also, if you should file a copyright application, you will have to make a statement under oath that the information provided about ownership is correct.

Try to determine ownership. It's not clear whether your great-uncle had a will (and the copyright wasn't mentioned in it) or whether he didn't have a will. If he had a will, and the copyright wasn't mentioned, it would likely go to whoever received the residuary estate. If he didn’t have a will, you would need to map out the family tree and determine what blood relatives were alive at the time your uncle died. For example, if your uncle had no will and your grandmother was his closest living blood relative at the time he died she probably became copyright owner under the rules of intestate succession (you can see how it works if he died in California). So, initially the copyright went to whoever received the residuary estate or by intestate succession. If it went to your grandmother, then, upon her death, the copyright would have passed according to her will, or if she didn't have a will, intestate succession would kick in again.

The diaries and the copyright. Your grandmother may have given you the diaries as a gift but giving you the physical possession of the diaries is different than giving you the copyright. It's the difference between giving someone a painting, and giving someone the right to reproduce the painting. That's why copyright transfers must be proven by a written document. By the way, the unpublished diaries are protected under copyright for seventy years from your uncle's death.

If this seems too confusing ... If this seems overwhelming, keep in mind that what you’re really trying to determine is whether there is a relative who will object to your claim of ownership or seek a share of any revenue from the publication. So, if you don’t expect the publication to be a major source of revenue, it’s likely you can proceed without bothering with most of these ownership rules because battles usually only arise when a big bankroll is at stake. If the diaries generate revenue and you're still unsure about ownership, put the money in an account for a period of several years in case someone appears out of the woodwork to challenge your claim. That good faith effort will likely go a long way towards resolving the matter.

Copyright applications. By the way, if you should file a copyright application, you would list your uncle as author and yourself as copyright claimant and under “transfer statement,” you would choose "By Inheritance" (as shown above). Also, if you should file a copyright application, you will have to make a statement under oath that the information provided about ownership is correct.

Wants to Use NYT Rotogravures

|

| Library of Congress WWI Rotogravure Collection |

Forced to Stop Using "Fortune 500 University"

Dear Rich: I just read your posting about "Fortune 500" being used by an author and it gives rise to a question. Last year I started an online information service about business issues and registered a domain with GoDaddy as " Fortune 500 University". I designed an original logo and font style that looked nothing like theirs and even posted my picture in the masthead. Later, I was assaulted by an over zealous lawyer from Time-Life who intimidated me into taking my web site down for copyright or trademark violation. Should I have allowed myself to be so intimidated? Unless you're the kind of person who likes root canals, tax audits, or head lice, we think you did the right thing. If you hadn't capitulated, you would have received a series of abusive letters from lawyers, each escalating in tone, followed by a mandatory domain name arbitration or a civil lawsuit. Regardless of whether you would prevail in either of these battles (and if we were a betting blog, we'd bet on Time-Life), we doubt you'd want to deal with the hassle.

How come the previous post said ... Our previous entry on "Fortune 500" explained that informational uses, for example -- using the Fortune 500 trademark or logo in a book or magazine (or in a blog) -- do not require permission. However, commercial uses such as creating an online information service, will likely run into problems. We know the difference between informational and commercial uses is slippery, but one dividing line you can use is to ask whether the mark is being used to analyze or discuss the associated goods or services (for example to reflect on or discuss the "Fortune 500" phenomenon). In that case, it is more likely informational. Finally, the use of "Fortune 500" as part of the domain name is going to set out a separate series of flags as it may be viewed as a form of cybersquatting.

How come the previous post said ... Our previous entry on "Fortune 500" explained that informational uses, for example -- using the Fortune 500 trademark or logo in a book or magazine (or in a blog) -- do not require permission. However, commercial uses such as creating an online information service, will likely run into problems. We know the difference between informational and commercial uses is slippery, but one dividing line you can use is to ask whether the mark is being used to analyze or discuss the associated goods or services (for example to reflect on or discuss the "Fortune 500" phenomenon). In that case, it is more likely informational. Finally, the use of "Fortune 500" as part of the domain name is going to set out a separate series of flags as it may be viewed as a form of cybersquatting.

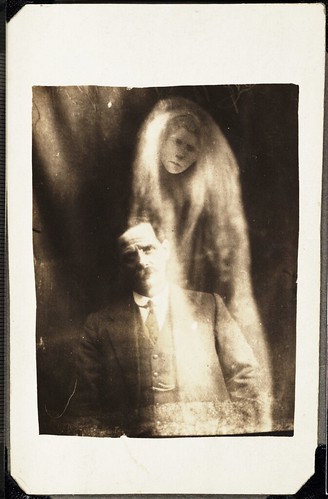

Needs Ghostly Permission

|

| from Spirit Photographs of William Hope |

The Conet Project. Yes, the owners of the Conet Project did sue Jeff Tweedy of Wilco for unauthorized use of their spooky recordings. (You can listen to the samples and the resulting recording here.) The case settled before a court could rule on the copyright ownership of these recordings. Akin Fernandez isolated and fixed the recordings and claimed copyright ownership. (By the way, since that lawsuit, the Conet Project's label has become part of the Free Music movement ... although we can't presume that means that copyright has been disavowed as well.)

He Wants to Create 'Book Summary' Business

I have an idea for a book summary business similar to the business book summary sites around the web, but I want to make sure I'm clear about the legality before I begin. In short, do I need permission from the copyright holder to create these summaries for sale? This is assuming that the summaries would be in my own words as much as possible and little to no direct quotations if needed. If it is your own expression and you're not quoting from the text, you should be fine. What can land you in hot water is extensive use of excerpts (or serious paraphrasing) and similar "copying" behavior as outlined in these literary fair use cases. BTW, here's an example of a lengthy, non-infringing summary, of one of our favorite new books.

Can I Trademark a Sports Star Nickname?

Dear Rich: What about the case where a fan comes up with a nickname for a sports star that is potentially a hot ticket? Can they trademark the nickname to protect potential rights to selling merchandise before the name gets traction? Probably not. As we predicted in a previous entry, applicants for the "Linsanity" trademark were dispatched by Jeremy Lin's lawyers (and they lost their $300+ trademark application fees, as well). The reason: use of the nickname on merchandise deceives consumers (who associate the nickname with the sports star, not the fan). This New York Times article goes into more detail. Even "unique" facial hair can form the basis for a basketball player's protectable trademark. Keep in mind that trademark law, unlike patent and copyright law, doesn't reward creative efforts, it rewards those who create a consumer association with a mark. So thinking up the trademark, or racing to the USPTO to be first to file, won't guarantee you trademark rights. BTW, in addition to trademark rights, you're also probably violating the right of publicity.

Band Wants to Use Samples of Poets

Dear Rich: My band wants to use samples in our CD. One of the sources is a compact disc of famous poets reading their work (compilation called "Lunapark 0, 10" recorded by subrosa (most all the authors are long deceased, but quite famous: James Joyce, Artuad, Appolinaire, etc.). I used bits and pieces and somewhat altered the snippets. Some are longer excerpts. Do I need to track the copyright down by author and their publisher/estate? There are two copyrights at work: one is in the poetry that's read (the literary copyright) and the other in the recording (the sound recording copyright).

What's public domain? If you wish to do everything according to the law, you should review the date of first publication for each copyright (the date of publication of the sound recordings is apparently indicated on the CD covers shown here). If you can determine those dates and then apply the rules found here, you'll know which recordings are public domain. You'll soon see the challenge with this, as pre-1972 sound recording, although not protected by federal la, may be protected under state or foreign laws.

Permissions. We suppose you could contact either: (1) Sub Rosa, the label behind the compilation or (2) Mark Dachy, the compiler of the collection, and ask whether permission was sought or needed. We think the pursuit of permissions for most of this material will be difficult. Generally, you can assume that newer tracks will be protected --- for example, the three tracks that are post 1972 --- and will require permission. Same for the tracks that include music (they incorporate a third copyright -- the music). As always, it really comes down to whether those who own rights will learn of your use (or care), and as a general rule, the older the work (say, for example, pre-1950s), the less likely you'll wake anybody up.

What's public domain? If you wish to do everything according to the law, you should review the date of first publication for each copyright (the date of publication of the sound recordings is apparently indicated on the CD covers shown here). If you can determine those dates and then apply the rules found here, you'll know which recordings are public domain. You'll soon see the challenge with this, as pre-1972 sound recording, although not protected by federal la, may be protected under state or foreign laws.

Permissions. We suppose you could contact either: (1) Sub Rosa, the label behind the compilation or (2) Mark Dachy, the compiler of the collection, and ask whether permission was sought or needed. We think the pursuit of permissions for most of this material will be difficult. Generally, you can assume that newer tracks will be protected --- for example, the three tracks that are post 1972 --- and will require permission. Same for the tracks that include music (they incorporate a third copyright -- the music). As always, it really comes down to whether those who own rights will learn of your use (or care), and as a general rule, the older the work (say, for example, pre-1950s), the less likely you'll wake anybody up.

Did I Infringe at ESL School Abroad?

Dear Rich, I taught at two for-profit, non-compulsory private English as Second Language (ESL) schools overseas that both used reading guides for the reading books that they assign the students to read or listen to as an audio recording. The guides included quotes, references, and pictures directly from the books assigned. The students had to buy the guides and novels (or audiobooks). I am not sure how the recordings were made, or if they were officially licensed by the publishers. I didn't bring this up with my employers for fear of losing my job. Was I using pirated material? It's possible you're asking because you want to report your ex-employers for copyright infringement. That's not unusual. Disgruntled ex-employees are a major source for reporting intellectual property violations (and they're often rewarded for their reporting).

In any case, we couldn't tell you with any certainty if a copyright owner could pursue an infringement claim. Most likely the unauthorized audio recordings constitute infringement but as for the rest, that depends on the amount taken, whether the use is excused as a fair use, whether the copyright owner can maintain a lawsuit in the foreign jurisdiction (or has a basis for suing in the U.S.), and who committed the alleged infringement.

In any case, we couldn't tell you with any certainty if a copyright owner could pursue an infringement claim. Most likely the unauthorized audio recordings constitute infringement but as for the rest, that depends on the amount taken, whether the use is excused as a fair use, whether the copyright owner can maintain a lawsuit in the foreign jurisdiction (or has a basis for suing in the U.S.), and who committed the alleged infringement.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)