“We may win when we lose, if we have done what we can; for by so doing we have made real at least some part of that finished product in whose fabrication we are most concerned: ourselves.”

“To be pulled in many opposite ways at once results negatively, but it is not the same thing as to feel no impulse at all. An ass between two bales of hay is said to have died of starvation, but not from indifference.”

“[L]life is made up of a series of judgments on insufficient data, and if we waited to run down all our doubts, it would flow past us.”

“The spirit of liberty is the spirit which is not too sure that it is right; the spirit of liberty is the spirit which seeks to understand the minds of other men and women; the spirit of liberty is the spirit which weighs their interests alongside its own without bias; the spirit of liberty remembers that not even a sparrow falls to earth unheeded”The last quote comes from a 1944 address given to a small crowd in Central Park. The speech was reprinted in Life, Reader’s Digest, The New Yorker and many newspapers. It struck a tone of tolerance that reverberated around the country and brought Hand unexpected attention and celebrity from the non-legal world.

Edward B. Marks Music Corp. v. Jerry Vogel Music 1 and Edward B. Marks Music Corp. v. Jerry Vogel Music 2. In 1907, the Edison Company released a performance of The Bird on Nellie's Hat. It was co-authored by Edward B. Marks and written in the 1890s. Marks also co-authored a song, “December and May.” In the early 1940s both songs became intertwined in a dispute that resulted in two separate lawsuits. One suit was about who had renewal rights to “December and May” and the other was an infringement action over “The Bird on Nellie's Hat.” In the latter, the defendant (the author of the infringing song) argued that both co owners (not just Marks) must sue him in order for the case to go forward. Judge Hand disagreed. He established the important legal principle, that either co-owner of copyright may bargain for, or litigate rights regarding the copyright, provided that the other co-owner receives an equitable interest in the results of the bargain or lawsuit. In the second case, Hand established that the same co-authorship principle applied for renewal as well -- that is, either co-owner may file the renewal of a copyright and that renewal benefited both co-owners, not just the co-owner who files the renewal.

Sheldon v. Metro-Goldwyn Pictures Corporation 2. Yesterday we discussed a case involving a Joan Crawford film, Letty Lynton, that infringed a play, Dishonored Lady. After resolving the issue of infringement, the case returned to the Second Circuit Court of Appeals and Hand again wrote the opinion. This time around the dispute was over how much MGM had to pay in damages. Until that time, the courts had taken the 1909 Copyright Act at its literal word; it stated the prevailing plaintiff in an infringement action was entitled to all of the defendant’s profits derived from the infringement. This was how the district court ruled and MGM appealed, claiming that only those profits attributable to the use (or portion of use) should be owed. Judge Hand acknowledged the difficulty in apportioning profits from a movie:

“Strictly and literally, it is true that the problem is insoluble. The profits from a picture consist of admission fees, which the playgoers pay because the picture attracts them with the hope of enjoyment. That enjoyment, which is one source of its further popularity, is made up of many factors: the actors, the work of the producer and director, the story, the scenery and costumes. The attraction and the hope which first draws them are principally aroused by advertisements, and the reputation of the stars and the producing company.”Despite the difficulty, Hand jumped in to the fray and after deducting certain MGM expenses, discounting expert accounting opinions, and apportioning a reasonable value to the use of the material from Dishonored Lady, he determined that the owners of the play were entitled to one-fifth of the film’s profits. In this decision, Hand ended the era of “all profits to the winner” and set the modern standard for copyright damages still used today. Although other judges have advanced theories of damages, Hand’s analysis is still considered the gold standard.

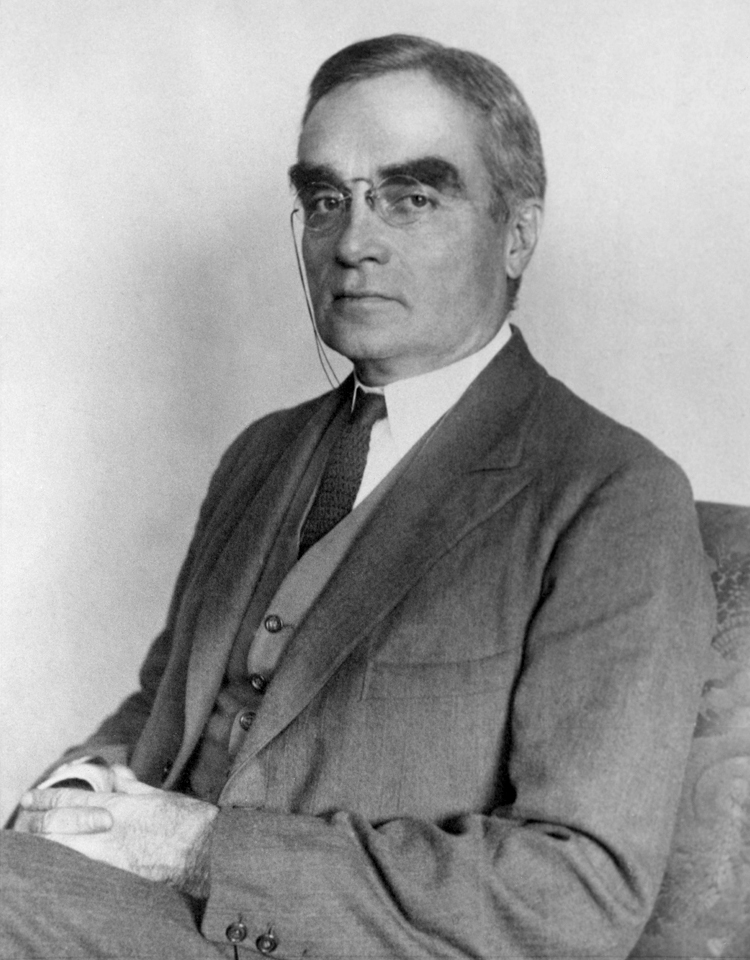

The Complete Hand. We've said a lot of nice things about Learned Hand during the past week but we’re not trying to paint him as a saint (can an agnostic be a saint?). There are a few eccentricities to report as well. Hand did not believe that the Bill of Rights should be considered “law” but merely "admonitory"principles. (He also advocated for the removal of the due process clauses from the Constitution and -- though strongly in favor of equal rights -- he criticized the Warren Court for its legal basis for striking down state segregationist laws.) He was a melancholic, highly self-critical and despised his own ambitions. When FDR failed to appoint him to the Supreme Court, he confided, "It was the importance, the power, the trappings of the God damn thing that really drew me on.” We’ve also seen he was a bit of a curmudgeon when it came to popular culture as evidenced by his distaste for Hollywood movies ("trivial"), comics ("silly pictures"), and popular music ("treacle"). But none of that means much compared to his accomplishments. This was, after all, the man who saved the Wright Brothers' patents and Superman's copyright. No fear of flying here. Thanks, Judge!